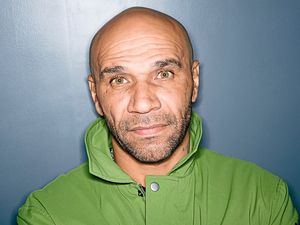

Goldie talks ahead of Birmingham gig

It takes us more than two months to track him down. And Wolverhampton’s one-man art-explosion Goldie makes it worth every last, frustrating, infuriating, needlessly-delayed second when we finally get through.

Clifford Joseph Price, the graffiti artist whose pioneering jungle and drum‘n’bass work made him the stand out dance artist of the 1990s, the actor-cum-household name who starred in James Bond, Snatch, EastEnders, Celebrity Big Brother and Strictly Come Dancing, is back.

The drug-taking, fast-car-buying, stripper-marrying, money-blowing, David Bowie-befriending, Björk-dating Member of the British Empire whose son was sentenced to life imprisonment for murdering a member of a rival gang has a new album out, The Journey Man.

He’ll be popping up at festivals during the summer, including MADE, in Digbeth, Birmingham, on July 29, before revealing all in November in a new autobiography. It promises to be an explosive read.

It’s taken Goldie almost 20 years to record The Journey Man. The 16-track double album is as uncompromising and visionary as his debut, Timeless, which changed the game back in 1995. He followed that in 1998 with Saturnz Return, an album about his tumultuous relationship with his mother, but to all intents and purposes, that was that. There was an EP in 1999, a couple of records released as Refige Kru during the noughties, as well as a soundtrack, but Goldie’s creative talents were poured into other projects.

He acted in the James Bond flick The World Is Not Enough and Guy Ritchie’s Snatch while also exhibiting his art in Berlin, Ibiza and other galleries in London. It caught the attention of the art world – he became mates with David Bowie and Prince Harry asked him to work on a bespoke piece for his wall.

He also moved to Asia, so that he can take his young kids to school on a motorbike before tucking into a morning full of yoga. Happy, happy days.

Goldie is a force of nature, a super-intelligent, ultra-creative kid from the wrong side of the tracks – Whitmore Reans, Heath Town, Walsall – who tore up the script that had been written for him and decided to write his own.

It’s been a while since his music made headlines. Saturnz Return feels like a long, long time ago. “It’s taken me 20 years to get my s*** together.

“Saturnz Return was about that relationship with my mother, I played it to her when she passed in a chapel of rest in Wolverhampton and thanked her for bringing me here. That emotional exchange within music never happens, really, not in electronic music. It might happen with arias or something, but it doesn’t happen with dance music. It’s all about the dance floor. But I have a conceptual mind. I knew that was going to be a difficult project but it served its purpose.”

And yet it’s the predecessor to Saturnz, Timeless, that made Goldie one of the most important acts in British dance. A groundbreaking drum and bass record with symphonic strings, deep basslines and female vocals, it is listed in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. Jaw-droppingly ambitious, its legacy remains firmly intact.

Goldie is proud of it: “I just felt like Timeless was never surpassed as a drum ’n’ bass album. If you can name one that’s better I’ll buy you a KitKat. But with The Journey Man, I’ve created a magnum opus. It’s bigger than Timeless.

“When a boxer comes back from retirement. They never come back and knock anyone out. But this album does. This isn’t an album where it’s decided on points.”

He’d prefer it if he didn’t have to compare it to Timeless, if there weren’t expectations, if he could drop The Journey Man in from the ether and smash all expectations out of the park. “I’m comparing it because I’m the artist and it’s my album. An artist is never going to say it’s not as good as the last, he’ll always say it is. But the opinions are subjective to audience. An audience might love Bowie’s early albums but not like Low. But then David told me he loved Low. He felt he’d been doing too much commercial stuff.”

And Goldie very definitely loves The Journey Man. It’s celebratory and joyous.

It might seem like a stretch to link Bowie with Goldie, but the parallels are clear. Both were artists in the truest sense, whose love of visual art infused all aspects of their work. And while Goldie has been nowhere near as profilic as the late David Bowie, they became good friends. “Bowie hated all his pop stuff but it allowed him to buy art. He gave me the Spencer book, about a black American artist who collected stuff. He turned me on to a lot of stuff. But he didn’t feel guilty about making pop because that allowed him to buy art. When he went back to Lazarus, at the end, he was looking up at the heavens in his lyrics.”

Goldie’s story is one of the most remarkable of all. From children’s homes in the West Midlands through stints in New York and Miami as one of the UK’s most celebrated exponents of graffiti art to rubbing shoulders with an exceptional list of musical collaborators including David Bowie, Noel Gallagher and KRS-One, Goldie has defiantly, definitively, done it his own way. The Journey Man is an extension of that. He’s practicing the dark arts and messing with the rules.

“When you play it, I can guarantee that your brain – and I’m no Mystic Meg – will take you to the idea of Timeless. It’ll be like going on an escalator. Your mind will try and compare it. It will affect your heart.

“I was going to call it The Proustian Effect. Because It was going to be called the Proustian Effect. It takes you to that Madeline Cake in your mother’s kitchen, or to playing football in 1977, or to getting oil on yourself when the chain broke on your bike. Timeless was 10 years of life through music. This is 35 years of influences. I’ve had fun with this. I was getting up at 5am and writing a song.”

The boy who would become Goldie was born Clifford Price on September 19, 1965, just as The Rolling Stones hit the top of the charts with Satisfaction. His dad Clement, originally from Jamaica, had been plying his trade as a foundryman in Leeds. His mum Margaret, who was born in Glasgow, was a popular singer in the pubs and clubs of the West Midlands. Barely more than a toddler, Goldie was just three when she placed him into foster care (though she kept his younger brother Melvin). He still remembers, he says, the day the social workers came to take him away. Over the next 15 years, he bounced between a series of foster homes and local government institutions around the Walsall area. His eclectic musical taste was forged, he reckons, in those same local authority homes listening to the sonic tangle of other teenagers’ record collections. “In one room,” he says, “a kid would be playing Steel Pulse while through the wall someone else had a Japan record on and another guy would be spinning Human League.” On rare visits to see his dad, he’d lie sprawled over the living room couch, listening to Jazz FM, marvelling at the lavishly-tooled ‘80s productions of Miles Davis, Pat Metheny, David Sanborn and Michael Franks, adding further layers to his complex musicography.

Art has always been his release. It’s his safe haven, his place for creative expression.

“It’s a canvass. It’s theatre. One thing I’m able to do is raise the deities. I don’t go into the studio without an idea. It’s 3D, 4D, what colours am I going to use? The music has to be painted first. Any bonus colours that happen are great. If there’s an arrow here and there I take it because that’s amazing.”

He has no explanation for the remarkable life he’s led.

All he knows is that as a kid he developed the irresistible urge to excel that has marked his inimitable musical career.

His first love was roller-hockey. He earned a place as goalkeeper in England’s national squad before the lure of music overtook the lure of sport. After discovering electro and hip hop, he grew his hair – the ‘goldilocks’ that won him his nickname – and joined a breakdance crew called the B-Boys in nearby Wolverhampton. He also discovered graffiti. “They called me ‘the spraycan king of the Midlands’,” he says proudly.

His talent was undeniable, bringing him to the attention not only of Britain’s Arts Council but to Dick Fontaine, producer of a Channel 4 TV documentary on graffiti. Fontaine’s 1987 film Bombin’ captured a visit to the UK by New York artist Brim Fuentes. Brim met Goldie and his B-Boys crew in Wolverhampton’s Heathtown before heading a dozen miles away to Birmingham’s Handsworth, where the producer filmed the aftermath of rioting that had left four dead, 35 injured and dozens of stores burned out. Several months later, Fontaine reversed the process and took Goldie to New York, introducing him to hip hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa. For Goldie, on his first trip abroad, never mind his first trip over the Atlantic, the Big Apple was love at first sight. Back in Britain, he begged, borrowed and saved until he had enough to fund a return trip to the Bronx. “I don’t know why it’s happened. If incentive and insight were sold in cans in Sainsbury’s or Iceland, the shelves would be empty. I don’t know. What you do today creates tomorrow.

“I can remember everything about the inner city. Mothers, fathers and sons are smoking the same Rizla, my brother in Heathtown, the money on the metre, people and sirens and could’ve/would’ve/should’ve. Pregnancies and babies. But you can’t define yourself by that, otherwise the small violins come out.

“People get bitter and turn against each other. For me, it was about getting on a plane and going to New York.”

And there he made his escape. And yet though he’s a global citizen whose home is now Asia, Goldie remains deeply connected to the place from whence he came. He was plugged into the Wolverhampton riots, watching as brothers tore up the city.

“The last riots, they weren’t real. They weren’t like Toxteth or Handsworth. You’ve got a geezer with £250 trainers and a bandana saying ‘life’s s***’ No it isn’t. Go to a favela in Sao Paolo where the geezer’s ain’t got no shoes, where the drug cartels are running it and your brother’s been shot in the head. When the riots happened, those people still had housing. I just put it into perspective, really, you know what I mean.

“The thing is, it’s going that way. It ain’t there yet, but it’s going that way. There’s murder mile in the inner city. 25 years ago, 35 years ago, it was all about a £2 draw and someone pulling a knife on you. It’s real time.”

Art – and music – were Goldie’s way out. Goldie found himself seduced by the sweet heart of the rave. Though it took him eight attempts to get entry into the club, at London’s Rage in 1991 he marvelled at the alternate sonic worlds being forged by Fabio and Grooverider behind the decks. “It really flipped me out,” he remembers. Soon he found himself in the orbit of Dego McFarlane and Mark Clair.

Their label Reinforced was in the vanguard of breakbeat, issuing astonishing records that stripped out boundaries and limits while setting the tone for the scene’s sense of adventure. At first he helped out doing artwork and a bit of A&R. But soon he was in Reinforced’s Internal Affairs studio watching intently as Mark and Dego recorded tracks like Cookin’ Up Ya Brain and Journey From The Light. “I was watching what they could do,” says Goldie, “trying to gauge the possibilities of the technology.” Soon he was getting involved. “I remember one session we did that lasted over three days,” he says, “just experimenting, pushing the technology to its limits. We’d come up with mad ideas and then try to create them. We were sampling from ourselves and then resampling, twisting sounds around and pushing them into all sorts of places.”

And for the kid who lay awake, gazing at the stars, through the window of a children’s home, growing up has brought some surprises. In 2012, he was selected as one of the BBC’s New Elizabethans, 60 people – ranging from David Hockney to Roald Dahl, David Bowie and Tim Berners-Lee – who have helped shape British culture during the reign of Elizabeth II. Four years later, he was awarded the MBE in the Queen’s New Year Honours. It’s acceptance, of course, on a grand scale. But at heart, he’s still the gatecrasher, amped-up on ideas, buzzing on nothing but love, hope and the certainty that, while his way might not be the easy way, it’s very definitely the path of a true artist.