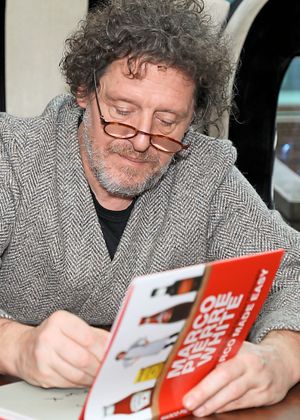

Marco Pierre White on the secret of his success

He’s the don of Modern British gastronomy who gave it all up to write books. Here he talks to Weekend about fame, family and festivities. . .

His advice for Christmas is simple. Eat out.

Marco Pierre White, the nation’s most charismatic chef, the winner of three Michelin stars and the only celebrity cook who keeps it real when the cameras are running, can’t understand why people would even think of cooking at home.

In a region full of affordable restaurants, there’s no reason to. We can book a table, enjoy starry service and not have to worry about who washes up.

In some ways, Marco’s advice comes as no surprise. After all, he’s an acclaimed restaurateur with one of Birmingham’s most successful restaurants, which is based at The Cube, in Birmingham. He visits the restaurant regularly through the year, enjoying the bright lights that dazzle from the iconic, skyline building.

“I come a lot to Birmingham,” he says. “Birmingham’s one of the great cities, without question. I always think of New York when I come to Birmingham because you can smell the talent. Birmingham is a city filled with talent. I suppose the industrial revolution started here and the talent never left.”

Whether it’s Christmas dinner or a Valentine’s Day meal for two, whether it’s a slap-up lunch or a special occasion, Marco believes we’ve never had it so good. As diners, people in the West Midlands are living through a golden era.

The nation’s gastronomic offering has changed during his lifetime. In many ways, he’s responsible for the fact that people can eat well when they go out. The so-called Godfather of Modern Cooking has helped Britain to change from being a gastronomic desert to one of the world’s most desirable locations. The revolution started in London, but the cooks who were responsible came from across the UK.

“When I think back to my training in London, 95 per cent of the cooks weren’t from London. They were from Birmingham and Leeds and Sheffield. They’d gone to London to learn. And then they left and went back to wherever they came from. And they took that knowledge back to cities like Birmingham and Leeds. Twenty to 30 years ago, cities like Leeds and Bristol and Birmingham didn’t have Michelin stars. Today they have great restaurants of their own.”

Though Marco is renowned for winning three Michelin stars – the culinary equivalent of scoring the winning goal in football’s World Cup or securing an Olympic Gold – he’s a big fan of casual dining. For him, food is about simplicity, rather than showing off. He’s catering to the masses, rather than the elite few who like nine-course tasting menus for £90 a pop.

“I’m in the business of selling a night out. I’m not in the business of selling 12 or 18 courses, where you’re not given a choice. I think what’s important is to give people a choice and also to allow people to cut their cloth accordingly. That’s where I think the future of dining out is, where you allow people to choose what they want, rather than going to Michelin-starred restaurants where you are forced down a road with no choice and having eight or 12 courses and playing a fixed amount of money.”

Face-to-face, Marco is a fascinating man. He keeps eye contact throughout and his stare is piercing. He has an intensity that few others can muster. And he’s ineffably cool; like James Dean or Jim Morrison, like Sonny Corleone or Steve McQueen. He’s still got his raffish good looks and a mop of curly hair. And he seems to talk in soundbites, like some sooth-saying prophet who has descended from on high.

When Marco speaks, others listen. After all, his distilled wisdom is as valuable as gold dust.

“As I said many years ago, the future of dining out was affordable glamour. As far as I’m concerned, food is three down on the list of priorities. Number one is the environment you’re sitting in. If you don’t feel comfortable, it doesn’t matter if you eat the best food in the world, you’re not going back. Number two is service. Number three is food of a very high standard at a fair price point that the average person can afford.

“The environment is the most important thing, then service. You could go to a restaurant tomorrow that has three stars and if you don’t feel comfortable, you won’t go back. You have to enjoy yourself. The Cube has a magnificent view. It’s like being Peter Pan. You look out across the town at night and it seems to be filled with fairy lights.”

Though Birmingham has more Michelin starred restaurants than any other British town or city outside London, Marco doesn’t visit them. You might expect a man with his culinary empire and his reputation would be checking out the young bucks at the city’s most prestigious eateries. But he doesn’t. He’d rather enjoy a pint and a decent steak at his own gaffe. He has no time for the formality of Michelin any more.

“We’re not there to patronise or dictate. I went to a two-star Michelin not so long ago, I was patronised. I don’t want to be patronised. The Michelin star restaurants of old were not like that. Today, they tell you what you’re eating, they tell you how many courses you’re eating. The waiters should wear balaclavas. They mug you without violence.

“I never eat elsewhere in Birmingham. When people choose to come to The Cube for their night out and they’ve worked hard all week, I have to respect that. Can you imagine if I’m down the road eating somewhere else: the guests would think ‘Who’s looking after The Cube?’ We can do 500 covers on a Saturday night. The 400th plate has to be as good as the first. Consistency is the most important thing. And consistency, in my opinion, is borne out of discipline. You have to be focused and stay focused and also be disciplined. Discipline begins with punctuality.”

We move on.

Marco has the most remarkable story of any chef. He was the youngest ever to earn three Michelin stars and he trained some of the most notable cooks in Britain, including Gordon Ramsay. He was born the third of four boys and left his native Leeds at the age of 16 to head to London. He had £7.36, a box of books and a bag of clothes.

Marco trained under the great Pierre Koffman while also working with Raymond Blanc and Nico Ladenis. He opened his own place in 1987, Harvey’s, and earned two Michelin stars. Soon after, he became the chef-patron of The Restaurant Marco Pierre White at the former Hyde Park Hotel, where he won three Michelin stars. He was 33, the youngest ever. He had worked for 17 years to achieve his ambition but gave it all up.

“As I said to my dear daughter, Mirabelle, who is a ballerina with the Royal Ballet: ‘You must understand one thing about your father, he was never ambitious as a young man. Never’.

"I’m still not ambitious. I was ruled by my fears, my fears of not being good enough, my fears of being sacked, my fears of going home to my old man and saying ‘dad, I’ve been sacked’. I was ruled by my fears of disappointment. That’s what motivated me.

“People think because I won three stars with Michelin that I must have been ambitious. But it was nothing to do with ambition. It was to do with fear of not being good enough. It was to do with my fear of failure. If I was ambitious, then it was ambition by default. It was all about doing my job well.”

When he’d achieved his ambition, he could quite easily have stayed behind the stove and retained his three stars. He’d achieved a level that only a handful ever achieve: he’d scaled Everest and K2. But, almost uniquely, he decided to quit. He’d had enough of the awful hours and the lack of a personal life. He wanted to re-invent himself and start again.

“I believe in integrity. On the day I didn’t want to cook any more I told the world I was retiring. I hung my apron up. I didn’t walk round in chef’s jackets pretending to cook when I didn’t cook. I didn’t put my name above a three star door, charge three-star prices and pretend to be in the kitchen when I wasn’t. At Birmingham, everyone knows I’m not in the kitchen. I tell the world. But if you have a three-star restaurant, a two-star restaurant, you have a duty to your clients to be behind the stove because that’s what they are paying for. When you’re paying that sort of money to have that man or woman cook your dinner, they have to be behind the stove. I accept that a chef is allowed to stray from the stove. But they must stay close to the flame.”

So why did he go? He was the biggest chef in Britain, the absolute don, why walk away when he was at the top?

“I had achieved everything. What was the point? I left home in the morning, my children were sleeping. I went home at night-time, my children were sleeping. I would work six days a week, sometimes seven, and I spent no time with my children. Sometimes in life, you have to be honest. I had three options: one, to continue with everything I had, my status and my position within the industry.

“Option two, I could have lived a lie, pretending I cook when I don’t, continuing to charge high prices when I wasn’t in the kitchen. But that would have brought into question my integrity and everything I ever stood for.

“So option three was to pluck up the courage, tell Michelin I was hanging up my apron on December 23, 1999, and get out of the kitchen and out of the guide. I had to accept that if I did that, I would be unemployed. I would no longer have any status.

“But one day, I had a little thought. That little thought was that I was being judged by people who had less knowledge than me. So what was three stars worth? Nothing. If the people who gave me those three stars had more knowledge than me, there would have been value in what they had given me. I am so happy I won my stars then, not today. In the old days, to win three stars you had to do it over a period of time, and not overnight. You had to prove consistency. Today, they put you straight in at three.”

And so he re-invented himself. He opened restaurants specialising in steak and ale, he published a number of best-selling books and he became head chef on ITV’s Hell’s Kitchen. The show earned stellar ratings as people tuned in to see a chef behaving authentically with the likes of Barry McGuigan and Jim Davidson, with Linda Evans, Adrian Edmondson and Anthea Turner.

Not that he enjoyed it.

“I hate TV. I’m just a showpony. It’s just a job. Not every interview you do is going to be enjoyable. You must write about things you don’t want to write about. But we have to make a living. It’s as simple as that. I’m very privileged and I meet a lot of lovely people but the bit I like least about my job is the TV side. The thing I like most is being in Bath, at my little farm. I have a hotel-farm, that’s what I like.”

He continues to cook. It’s a way of life. For Marco, good food is all about making it taste of what it’s supposed to taste of. It’s about respecting Mother Nature. It’s about using recipes as a guide, rather than a commandment.

“The greatest lesson I’ve learned in my life is to keep it simple.

“I had no option but to cook. My father, grandfather and uncle were all chefs. I came from humble beginnings, a working class boy. Had my father been a miner, I’d have gone down the pits. Had my father worked in the factory, I’d have gone there. We didn’t have options those days. We didn’t have a sense of entitlement, like a lot of youngsters now. We did what our parents told us.”

He wouldn’t change anything. For all of the controversies and public rows, he wouldn’t change anything.

“Had I not made all those mistakes, I wouldn’t be the boy I am today. And the beauty of making mistakes – and there’s nothing wrong in making them – is this: you have to have the humility within yourself to take the knowledge from the mistake. It’s about acceptance. Take the knowledge out of the experience, out of the mistake.”

Marco’s still living and still learning. He remains the most fascinating figure in British gastronomy, a maverick, a one-off, a man whose opinions and experience still count. Within hospitality, he is revered. And he still lives for the simplest things – a decent pint, a good steak and the company of his friends.

Andy Richardson