Ludlow's a ghost town after tragedy

One hundred years ago there was a terrible massacre in Ludlow which has gone down in history.

You will probably not have heard of it, because it was not in Ludlow, Shropshire – but Ludlow, Colorado.

And the events of April 20, 1914, were a dramatic and violent clash between corporate power and striking workers.

The event was to have a profound and lasting effect in the United States and seriously damaged the reputation of one of its most powerful business figures, John D Rockefeller.

Unlike our Ludlow, which is still a thriving market town, all that remains of Ludlow in Colorado today is a ghost town.

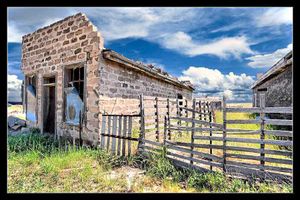

The Ludlow Monument to the dead stands in a bleak landscape amid wandering herds of cattle, a solitary windmill, farmhouses, railroad tracks, and the crumbling ruins of stone houses.

The legacy of Ludlow, the deadliest labour dispute in American history, was a series of changes which improved the lot of workers.

Yet the price was high. Among the dead were two women and 11 children.

The scene of the tragedy was the mines of the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron Company.

The miners and families were from diverse backgrounds.

They included Italian, Greek and Slovenian immigrants who had fled Europe and were looking for a better life in the United States of America.

The strike began seven months before the massacre.

The miners were seeking a package of improvements, ranging from fair pay and eight-hour working days to the right to see the doctor of their choice.

Coal operators immediately played hardball and evicted them from their company-owned homes.

In response, the 1,200 miners and their families pitched tents at Ludlow.

They were nearly all immigrants, and the camp was a cosmopolitan place, with 24 languages spoken.

There was a school, hospital, playground, a grid of streets, and a system to distribute firewood.

Among the aggressive measures taken by agents hired by the coal companies to try to break the strike was random sniping at the camp.

Families dug pits underneath their tents for protection.

Violent incidents and tension rose until April 20 brought a bloody climax. A gunfight broke out.

It culminated in the National Guard being called out and a strike-breaking militia entering the camp and setting fire to tents.

The women and children who were killed had been sheltering in a pit beneath one of the tents.

In addition to their deaths, about 13 others were shot dead during the fighting, figures vary.

Although 66 were to die before the strike was crushed, it was the deaths of those women and children, the youngest of whom was just three months old, which caused shock and outrage across America.

Rockefeller made things worse by trying to justify what had happened.

An incidental effect was what is seen as the birth of corporate public relations, he hired a former reporter to try to improve his image.

In the short term, the deaths were for nothing, as the strike was broken with no significant improvement in the miners' pay or conditions.

In the longer term, there were a series of changes attributed to the massacre.

Congress responded to public outcry by directing the House Committee on Mines and Mining to investigate the incident. Its report, published in 1915, was influential in promoting child labor laws and an eight-hour working day.