Riverbank works uncover ruins of homes from Shropshire landslip disaster

[gallery] The remains of eight houses swamped by a landslip in Shropshire 62 years ago have been uncovered on the banks of the River Severn.

The community was torn apart when great swathes of Jackfield, near Ironbridge, were destroyed during the infamous landslide of 1952.

Now, 62 years on from the disaster, the remains of eight of the 27 houses engulfed by the landslip have been uncovered after decades buried on the riverbanks.

The footings of the properties were discovered during the excavation of the riverbanks as part of a £17.6 million stabilisation scheme to protect the area from future landslips.

Archaeologist Shane Kelleher, from Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, said he was amazed at how well preserved the remains were after such a long period of time.

"It is a very exciting find," he said. "We were expecting to maybe find a bit of rubble. We are surprised that is was so intact."

The precise age of the houses is not known, but Mr Kelleher said they were clearly shown on records dating back to the early 19th century.

Ron Miles was a young guardsman at Buckingham Palace when he noticed a poster outside a cinema in central London in 1952.

"Village slipping into river," said the sign. Ron's mother had told him in letters from home that there had been problems with landslides in his home village of Jackfield, near Ironbridge, but nothing could have prepared him for what he would see on the Gaumont and Pathe newsreels.

"In the roar of these floodwaters can be heard the sentence of death, not of a man but of a village in Shropshire," said the Pathe voice-over.

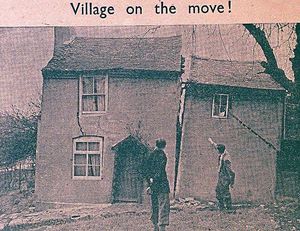

The images he saw looked like scenes from World War Two with footage of crumbling buildings and gaping cracks in walls.

The first sign of the problem came when workman on the Severn Valley Railway noticed that the line had started to move.

"They would be there every day with large crow bars, trying to move the track back," recalls Ron, who still lives in Calcutts.

However, it was during the early months of 1952 that people started noticing cracks in their homes. By April Jackfield had become a virtual ghost village.

Dozens of people were evacuated from their homes, which became almost cut-off from the outside world as the roads heaved and buckled.

The problem was generally blamed on the clay mines which once dominated the area, but these days it is believed that the comparatively young geology of the Ironbridge Gorge was probably a bigger factor.

A total of 27 houses were lost and about 17 families were moved to council houses in nearby Broseley.

But that was not to be the end of the problem, for decades

people had to contend with a track made of wooden sleepers to cope with the heaving ground to get to Jackfield, until today's stabilisation project.

Bends in the walls, where the foundations gave way, are clearly visible, and Mr Kelleher said the remains show the changing styles in interior decor over the centuries.

Neal Rushton, of Telford and Wrekin Council, said that where possible the foundations would be preserved and sealed beneath the embankment before landscaping. However, some of them will need to be removed to make way for the giant steel poles which will secure the bank for at least the next 100 years.

The work began in October 2013, and it is expected to be completed by March 2016.

Clues to life lost in huge landslip:

It began with movement in the railway line. A short while later, cracks started appearing in the houses. Within a few months, the entire village was torn apart as 27 houses began sliding towards the River Severn.

Life in Jackfield, near Ironbridge, would never be the same again.

The infamous landslip of 1952 wreaked havoc in the close-knit community, which was dominated by its famous tileworks. And now remains of the houses have been rediscovered after more than six decades buried in the hillside.

A distinctive Romanesque-style mosaic floor, an ornate bread oven in an outhouse, and even an old kettle have been uncovered by workers on a £17.6 million remedial project to ensure such a calamity will never happen again.

At the moment 2,000 steel poles, or piles as they are more correctly known, are being sunk into the banks of the Severn to halt movement in the land. Project manager Neal Rushton said within six months of the scheme being complete, the landslips which had blighted the village for centuries would be stabilised for at least the next century.

Mr Rushton said the piles were designed to bend slightly during the first six months of construction, but after that would be completely stable. Electronic sensors will be installed beneath the earth's surface to monitor any movement.

Shane Kelleher, an archaeologist with the Ironbridge Gorge Museums, said the houses were an exciting find and he was surprised so much had survived.

He said: "It's a fascinating social history. It shows how tastes and styles have changed over the centuries.

"One of the things which strikes you is there are very many nice tiles, which suggests that the houses may have belonged to people who worked at the tile factory.

"Jackfield was once a world centre for high-quality tiles and the people who worked there would probably have been given the tiles as a bonus to supplement their wages or would have been allowed to buy them very cheaply."

One of Mr Kelleher's favourite features is the black-and-white mosaic-style floors in what he believes would have been the kitchen of one of the houses.

"That style of floor probably dates back to the late 19th century," he said.

"I would be pretty glad to have something like that in my house, so the people who lived here would probably have been very proud of it."

In one of the houses, there is a trace of linoleum which has been laid over a cream-tiled floor, showing the changing tastes in interior design.

There is also a small, plain tiled floor with an unusual upward slope, which Mr Kelleher believes would probably have been designed for a specific purpose such as meat preparation.

Another interesting feature is the bread oven with distinctive tulip-patterned tiling. It is set behind the main footprint of the houses, leading Mr Kelleher to believe it was probably a shared outbuilding.

Kinks and bends in the walls show the damage which would have been caused to the properties during the landslide, and the floors of many of the houses also show bulges in the floor where the ground rose beneath them.

"We found an old kettle, but there wasn't that much stuff left behind," said Mr Kelleher. "The people living here had a few months to get their belongings."

Mr Kelleher said some of the artefacts would be taken to the museum, although not all the remains will be preserved.

Mr Rushton said where possible, the foundations would be sealed and preserved for future generations, but others, which were in the way of the structural preservation work, would be dug up and used as landfill.

He said care would be taken to ensure that nothing of archaeological importance would be lost.

The project is being funded with the help of a £12 million contribution from the Government with the rest of the money coming from the council.

The work is due to be completed by the end of March 2016.