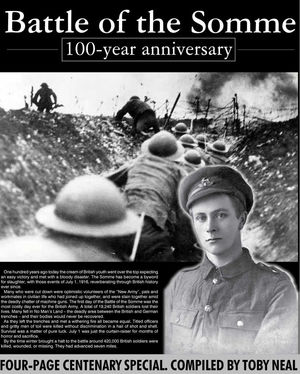

Battle of the Somme 100th anniversary: Shropshire heroes who won Victoria Cross

One hundred years ago today the cream of British youth went over the top expecting an easy victory and met with a bloody disaster.

The Somme has become a byword for slaughter, with those events of July 1, 1916, reverberating through British history ever since.

The Somme campaign, which lasted until November 1916, was to yield a number of Victoria Cross heroes with Shropshire links.

Thomas Orde Lawder Wilkinson was born at Lodge Farm, Dudmaston. He emigrated to Vancouver Island, Canada, in 1913, and enlisted with the Canadian Army on the outbreak of war.

Lieutenant Wilkinson was later commissioned into the 7th Battalion The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. He was awarded the VC posthumously after he was killed at La Boisselle on July 5, 1916, aged 22.

He and two of his men dashed forward and used an abandoned weapon to hold the enemy at bay. Later that same day, when the British advance stalled during a bombing attack, he pushed his way forward to find five men halted by a solid block of earth, over which the Germans were lobbing grenades. Wilkinson mounted a machine-gun on top of the parapet and quickly dispersed the enemy bombers. During the second of two attempts to bring in a wounded man from no man's land, he was killed. His body was never recovered.

Brigadier General John Vaughan Campbell of Oswestry became known in the popular press as the "Tally Ho VC", because he rallied his men under enemy fire by blowing a hunting horn and giving the traditional hunting cry.

With his men being cut down in their droves Lieutenant Colonel Campbell – he was subsequently promoted – got out his hunting horn at Ginchy on September 15, 1916. Later in the day he again rallied the survivors of his battalion and led them through very heavy hostile fire.

Major Billy Congreve was 25 when he was killed on July 20, 1916. His family had lived at West Felton, near Oswestry, since his early childhood – they owned The Grange. Congreve had been serving in the Rifle Brigade and his VC was awarded "For most conspicuous bravery during a period of 14 days preceding his death in action."

Fifty years ago, the Rev Arthur Procter of Shrewsbury was one of seven winners of the Victoria Cross invited by the Minister of Defence to attend 50th anniversary Battle of the Somme ceremonies in France. Mr Procter, who lived in Mytton Oak Road, was chaplain to the Shrewsbury branch of the Royal British Legion and had won the VC on June 4, 1916, for dashing out under heavy fire to save two wounded British soldiers lying in full view of the enemy. The incident, as it happens, was not on the Somme, but near Ficheux, south of Arras.

Mr Proctor was the first British soldier to be decorated with the VC on the battlefield. Hailing originally from Bootle, he lived in Shrewsbury relatively briefly in the 1960s, and died at Sheffield in 1973.

Body of Harry, 22, was never found

They never found the body of Private Harry Lister. The 22-year-old lad from rural Shropshire, who was forging a career as a teacher before answering the call to arms, went over the top with his comrades on July 1, 1916. He was one of nearly 20,000 British soldiers to die that day.

His parents, Thomas and Clara, hoped against hope that one day he would come home.

"I can remember my father saying that even after receiving the telegram saying he had been lost at the Battle of the Somme, Harry's parents used to hope that their son might turn up. They used to look up the road for him and things like that. At the same time, I seem to remember him saying that losing their only son totally shattered them," said Mrs Julia Thomas, Harry's great niece, who named her own son Harry after him.

Harry's name is recorded on the Thiepval Memorial for the missing. And there is a plaque in his honour at what was his local church – Bourton church, near Much Wenlock.

The family lived at Woodhouse Fields at Bourton, where they had a smallholding, and Julia, who lives at Kinnerley, near Oswestry, has been looking into the background along with her sisters, and also brother Graham Williams, who lives in Broseley.

There are some items of memorabilia to help. They include a photograph of Harry, and also the "dead man's penny," a memorial plaque which was given to the next of kin to honour their sacrifice.

As to the circumstances of his death, he was in the 1/8th Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. This was a Territorial Army battalion, people who had jobs in civilian life and were doing their bit for their country. These soldiers went over the top on the Somme in the first wave at 7.30am to attack a German strongpoint known as the Quadrilateral, incurring grievous losses. The position was taken, but proved untenable and they had to withdraw. Harry was not among the lucky ones who came back. The following day the battalion could only muster 47 men out of 600.

"He was my great uncle, the brother of my grandmother, May. They were the only children and both May and Harry went to Bourton School. In the 1911 census, when Harry was 17, it's got him down as a probationer teacher. When they finished school at 14 or 15, if they were scholarly, they would sometimes become like an under-teacher, and I believe that's what happened with Harry. I did think he had gone to teach at Coalbrookdale School, but having talked with my sister we think that he stayed as a probationer teacher at Bourton. The headteacher had a son called Harry who was killed, I think falling off the school wall, and we believe 'our' Harry became his protege, and he encouraged him to go into teaching," said Julia, who is herself a teacher.

Harry went to train at Saltley College, in Birmingham, probably to get his teaching qualifications and it seems being in that area was the reason he joined the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in late 1914, rather than a Shropshire regiment. Julia has no information about his service up until the time of his death.

"His parents were given a blanket after his death. Apparently supposedly they wrapped the soldiers' bodies in these blankets, and the family would get the blanket. Although they never found Harry's body, they still got the blanket. I have no idea what happened to it. I do remember a grey serge blanket, but whether that was the one, I have no idea."

Brother Graham, whose middle name is Lister, carrying on the family name, also has a memory of there being medals, and he also has the "dead man's penny." Graham said: "Harry was my dad's mother's brother. We were told about him by my father Colin Williams when he was alive and I asked my mother bits over the years. She died two years ago. That's how I came to find these things in an old box.

"She gave me the dead man's penny in 2006 when she was sorting things out. There were some medals when we were kids. We kept playing with them. She must have thrown them away. My mother was a bit like that."

One of the items Graham has is a bit puzzling. It is a letter written in pencil from "Somewhere in France" on April 8, 1915, to "Edith" signed by "Your affect. cousin, Harry" who gives his details as "2014 Pte. H. Lister, A Company, No 4 Platoon, 1/8 R. Warwickshire Regt..." He tells her: "We have been out there some little time now, but have not yet experienced anything very exciting, though we have had a short period in the trenches."

The puzzling aspect of it is that if, as it seems, 2014 is his service number, it is not the same service number of the Harry Lister from the same battalion killed on the first day of the Somme, which was 305160.

Service numbers could, however, sometimes be changed. Or perhaps a passage in the letter gives a clue to a possible explanation: "I was glad to hear that Harry had volunteered for France and if he comes out I hope it may be possible to see him." Were, then, there two related Harry Listers who served in the same battalion?

Harry's loved ones do not seem to have talked about him much, but the grief must have run deep.

Julia said: "I can remember my father telling me that when he was a smallish young lad he used to go to Harry's parents' farm at holiday times. One day, in the cow shed, he found a bicycle strapped to the wall and, being a young lad, got the bike down and dtook it to his grandparents who were really upset and horrified, because it was Harry's bike.

"Harry had a sweetheart when he went to war, although I don't know if they were engaged. Her name was Violet. My sister has some postcards he sent to her. After the war, we were told, she went to Thiepval and saw the commemoration plaque. I too have been out there and seen the memorial with his name on it. I was told by my aunt, my late father's sister, that she did eventually marry again but she had Harry's photograph still in a frame."

Julia finds it interesting that Harry did not follow his father into farming, and instead wanted to be a teacher.

"I think they were very supportive of that. He was talented, quiet – just a very pleasant young man."

A hundred years on, Harry's family continues to cherish and honour his memory. Graham said: "Am I proud? Oh God, yes. They were young lads going to war. They didn't have a clue what they were up against."

The Shropshire Star's Shirley Tart writes:

Surely the irony can't have been lost. A hundred years ago and half way through a war which was supposed to end all wars, we are busy breaking up a European Union which has worked for peace, if not on some other ways, for a couple of generations.

Thank God we have had nothing on our home ground in our lifetimes like the Battle of the Somme. And please God we never will.

We have honoured the Churchillian cry that jaw, jaw, jaw was better than war, war, war and most of us believe it still is.

Because on July 1, 1916, all those in the middle of the battle rose up from their bunkers, went over the top and 19,240 British soldiers died on that day. It was carnage, many bodies were never recovered, many still remain unknown deep in the graves of the Somme.

By now, after a week of remembrance, more of these facts are known to more people than they ever were before.

How painful, though, that the deaths of more than a million young men from Britain and France are being commemorated at this particular time when we are leaving rather than helping rebuild the Union.

Picardy was the area chosen for the attack, in the sector where the French and British armies adjoined each other on either side of the river Somme with attacks by both armies from either side of the river.

Now, within days after the referendum which has split the nation, we watch with tears of regret and pain as war casualties are remembered.

Young men, strong, true and brave.

At the same time, we have the cringing sight of our own lightweight politicians vying for position in not always the most seemly of ways and already scrapping in the wake of last week's critical vote.

We can't and should not try to live in the past. But the past can teach us a thing or two – not least that unity, however irritating it might sometimes be, is better and safer than the splendid isolation which makes nations feel they are more capable of going for some sort of special glory they can call their own.