John McCarthy: I will always be the former Beirut hostage

John McCarthy was chained by his ankles in a small, cramped cell with fellow hostages Terry Waite, Terry Anderson and Tom Sutherland when one of his captors entered the room.

With no explanation, he confiscated the radio they had been allowed to listen to, and started unlocking his shackles.

"I had no idea why he was doing that, and wondered what was happening," recalls Mr McCarthy. "It was not something they normally did. They would undo the chains in the morning to allow us to go to the bathroom, but they had already done that earlier. Then the guard said to me 'come on, John', so I hugged the others and left the room."

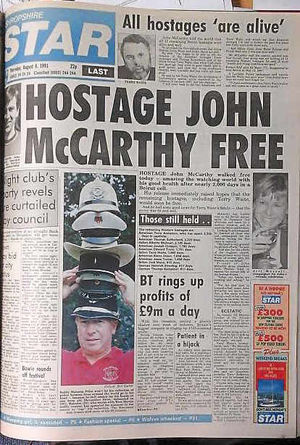

After 1,943 days in captivity – nearly five years and four months – he was about to become a free man.

That defining moment in his life happened 25 years ago on Monday.

Much has happened since Mr McCarthy was finally freed from his nightmare ordeal, but he still paints a remarkably lucid picture of his final hours at the hands of the Lebanese terror group Islamist Jihad. And he speaks of his sadness at how more then 30 years since as a young television journalist covering the civil war in Lebanon, that the Middle East continues to be a hotbed of unrest and fighting.

"The sad thing is that most of the people there are lovely, they are so welcoming," he says.

"There are vast areas of Iraq and Syria for people to live side by side, there is no lack of space, even Israel and Palestine there is enough room for everyone. You hope that one day they will all learn to rub along and learn to trust each other, but you have always got these groups that want to be dominant and that are so steadfast in their views."

Expansive and eloquent, he tells how his release came as a total surprise to him and his fellow hostages.

"Brian Keenan had been released a year earlier, and the conditions really were pretty decent at that time. We had a radio and heard that Islamic Jihad were going to send an envoy to the United Nations, and were preparing to release one British and one American hostage.

"We assumed that Terry Anderson would be the American, he was the longest serving, and they also had the former Spitfire pilot Jackie Mann, he was in his late 70s, so we assumed on humanitarian grounds that he would be the British hostage who would be released, and we were all excited about that."

It never crossed Mr McCarthy's mind that the young television journalist – who had been on his first overseas assignment when he was kidnapped in January 1986 – that he would be the special envoy he had heard about on the radio.

He remembers a dramatic change of mood the moment he left his cell.

"They took me to the guards' room, and in their minds I was already a free man, and they were pretty well at ease once we were out of the main cell. There were no longer bearing guns or anything like that.

"I told them to give the radio back to the others, but they said 'you're going home, won't that upset them?' and I said 'no, they will be excited about it', and they did give them the radio back."

His captors then explained that he had been chosen because he seemed to have adapted well to his time as a hostage, and they wanted him to deliver a message to the then United Nations Secretary-General Perez De Cuellar.

"They asked me what I thought they should put in it," he recalls. "I said I'm obviously a bit out of touch with what is going on, but my instinct would probably not be to write a long Islamist account of how they were angry with the West, because they would probably have a pretty good idea what their views were on that subject. I suggested they instead give a detailed record of who they have got hostage, who is alive, any Israeli troops, and what it is that they want. They said that sounded good to them."

Mr McCarthy was blindfolded and taken in the boot of a car to a flat in a different part of Beirut, where he was given clothing, and allowed to shower and shave. There was also a surprise gift for the departing hostage.

"They gave me a watch. I hadn't had a watch for five years, and I was like a kid. I've got a 10-year-old daughter now and if you give her something like a watch or a toy she looks at it and talks about it all the time and I was like that."

He was handed over to the Syrian army and describes a memorable journey to Damascus in the custody of a high-ranking Syrian officer.

"After five years in a tiny cell, here I was in this general's open-top Mercedes sports car," he says.

"He lit his pipe and I remarked 'that smells good', and he said 'do you smoke?'

"I told him I did and the general just raised his hand up out of the car and this other car raced up alongside us. I realised that was one of his bodyguards and he said the Arabic word for 'smoke' and suddenly they were raining down cigarette packets on us."

It was a very different experience from the moment he was snatched on his way to Beirut Airport more than five years earlier. As a 29-year-old learning the ropes of TV production, he had gone to Lebanon to cover the civil war that had been unfolding.

"At the time I thought it was terribly exciting," he says. "Then a number of Westerners started being picked up and no-one knew why.

"So it seemed like a good idea to get out of town until the situation became clear again.

"I was on the way to the airport, thinking about getting home later that day, seeing my girlfriend, phoning my mum and dad, when suddenly a car raced past us, slapped on the brakes and screeched to a halt completely blocking the road.

"And I remember sitting there in the front passenger seat, a couple of colleagues in the back. We didn't say a word, just sat there watching this car as the back doors slowly opened and this guy got out; this very big, tall young guy, big bushy beard and a machine gun.

"He strolled over to the bonnet and stood there staring at me, then came round to my door, yanked it open and grabbed me by the back of my neck, threw me in the back of this car and it raced off."

He describes the experience as like being in a film and it was only when the gunman violently forced his head down in the back of the car, so he could not be seen by other people, that the enormity of his situation dawned on him.

A week earlier, Brian Keenan, an Irish lecturer who had been teaching at the American University of Beirut, had also been kidnapped.

After spending two months in isolation, the blindfolded, dishevelled, bearded Irishman was thrown into a cell with Mr McCarthy, and the two became the closest of friends: "He was my strength and my soul mate. Without him I don't think I would have made it."

Mosquitoes made it impossible to relax. He was given a candle and matches, but they were attracted by the light.

"They made a phenomenal row, determined and aggressive, attacking me where my skin stretched tightly over my bones, on my ankles and on my wrists. The pain was excruciating and I soon learned that it was fatal to scratch the bites.

"Instead I would ineffectually dab them with water or spit in an attempt to take the heat out of the stings. Sometimes it got so bad that I had to get under the filthy blankets to hide from the hordes."

He says that for much of his time as a hostage, one abiding concern was whether he would be able to return to his job on his release.

Almost a year to the day after his capture, the Archbishop of Canterbury's special envoy Terry Waite travelled to Lebanon in an attempt to secure the release of Mr McCarthy and three other hostages.

Having been promised safe passage to meet the hostages, who he was told were ill, he agreed to meet their captors, but they broke his trust and took him hostage too.

"I think they were suspicious with his connections to Oliver North and they treated him very roughly," says Mr McCarthy.

At the time, unbeknown to Mr Waite, American colonel North was embroiled in the Iran-Contra scandal in which the US government sold weapons to the Iranians in a clandestine attempt to get the hostages freed.

Mr McCarthy recalls his first meeting with the envoy in the boot of a car: "I was just lying in the boot of this car, when suddenly this great big thing was thrown in on top of me.

"I then heard a voice in this I think Lancashire accent (Waite is actually from Cheshire) that said 'it's a nice big boot', to which I replied 'it was until you came here'. We then introduced ourselves to each other and we were just able to shake hands, in that frightfully British way."

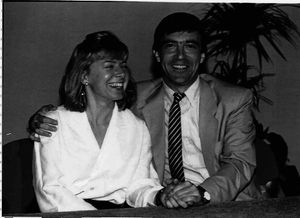

Mr McCarthy has since returned to Beirut where his visit attracted much press attention. He also still keeps in touch with Terry Waite and Brian Keenan, as well as his fiancee at the time, Jill Morrell, who campaigned tirelessly for his release throughout his captivity.

Despite the public's appetite for a happy ending, they never married, and parted amicably in 1994. Mr McCarthy went on to marry Anna Ottewill in April 1999.

Mr McCarthy is disarmingly open about his relationship with Jill Morrell saying throughout his time in chains he wondered whether their relationship would endure on his release.

"Things didn't work out with me and Jill, whether that was because of my experience or not, I just don't know," he says.

"But I will always be grateful for all that she did for me, there will always be that bond."

A quarter of a century on, he says he is now fully recovered from his ordeal, and is finally at ease with the public profile that came with it.

"I went from being just an ordinary bloke to suddenly being the most famous man on the planet, and everywhere I went people recognised me and came up to me," he says.

"People used to tell me their stories, they used to say how great they thought I was, which I felt uncomfortable with, because I didn't do anything.

"But now I see it is nice that they take the trouble to talk to you, and it has enabled me to do many things in work which I would not otherwise have been able to.

"I will always be former Beirut hostage John McCarthy, but I'm now totally at ease with it."