Heroin – and the war against drug crime in the West Midlands that can never be truly won

It is a long, winding and perilous journey from the suffocating heat of the Golden Triangle’s poppy fields, a near hypnotic carpet of bright red petals, to the wet cement of fire-fly backstreets in the West Midlands.

It is a secret journey – punctuated by stop offs, swapped couriers and juggled transportation – paved with, and paid by, misery.

From starting point in the beautiful, if battle scarred, parcel of land that nudges Thailand, Laos and Myanmar, to the grime of our region’s underbelly, it is a journey taken by the first mules to bring heroin to our doorsteps on an industrial scale.

It is a journey of some 6,000 miles and, by the end, the deadly cargo will have been teased into very different commodities from the white latex that drizzled down bloated poppy seed pods, each drop saturated with pure, raw opium.

Jungle laboratories turned the soporific sap into a granular grey substance that has the pungent smell of vinegar. This is the brown sugar Mick Jagger sang about. Known simply as Number Three by those that cultivated the poppies, it is coarse and for smoking.

Number Four – cooked to the colour and smooth texture of talcum powder – is even more profitable. It is China White. It is pure enough to flow through veins.

And it feeds the habits of those who need it in our urban towns and cities, as well as supplying the county lines operations that take drugs into the likes of Shropshire and Staffordshire.

The then Custom and Excise’s first major blow in the war against heroin – a war that can never truly be won – was struck in Walsall, a town once famed for its saddle-making industry.

And it was a bust that spanned both the West Midlands and Far East, with specialist officers sent to Hong Kong to prevent hundreds of local people becoming hooked on the highly addictive, synthetic drug’s barbs.

It was struck only months after the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act was brought into force – a slice of legislation that provided positive proof heroin was no longer just ruining the lives of rock stars. Ordinary people were becoming poppy impregnated addicts drawn, in increasing numbers, to the flame of drug fuelled destruction. First, they shed their dignity, then their good name, then their family. Disease and death followed.

It is a long, winding and perilous journey from the Golden Triangle to a Walsall restaurant.

Li San Shun and Li Ma Fat, a worker in his eatery, almost made it, weighed down by a staggering 50 packets of brown sugar: a near cargo of the Class A drug. The biggest haul to date.

The pair were lifted in June, 1972, after returning home following a trip to Hong Kong, the drug cache hidden in a heavy quilted bedroll. They denied everything. They even denied knowing each other.

Their lack of co-operation spelt a long journey for Brian Clark, Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise intelligence officer, sent to Hong Kong on an evidence gathering mission. There he liaised with fellow Customs officers and hard-nosed narco squad members.

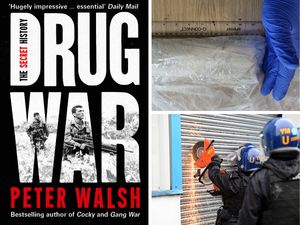

“They were all colonials,” he recalled in best-selling books Drug War: The Secret History by former Coventry Telegraph reporter Peter Walsh.

“Aussies, tough Canadians, Northern Irish – very hard men. They thought I was a soft Englishman.”

Peter may not have had their rough-edges, but he was meticulous and gathered the vital details needed to sever the supply line to Walsall. Lin San Shun, aged 53, was jailed for nine years, 36-year-old Li Ma Fat for eight.

Mr Clark said: “It was the first seizure, the first charge, the first successful prosecution. I was just pleased I pulled my weight.”