Mark Bridger: 'Fog of evil' surrounded April Jones's killer

Neil Samworth was a seasoned prison officer, in his own words “a big lad” who was used to handling himself. But nothing could prepare him for the task of guarding child killer Mark Bridger, whose murder of five-year-old April Jones rocked the nation.

“It’s like there’s this black, horrible fog around him that infects your body,” says Mr Samworth, who spent 10 months guarding Bridger.

“I can’t say anything specific, people like that just get under your skin, it’s difficult to explain.”

It was during his time working on the healthcare wing of HMP Manchester, more commonly known as Strangeways, that Mr Samworth came into contact with Bridger.

Even now he says the very mention of the paedophile still makes him shudder.

Bridger, of Ceinws, near Machynlleth, was told he will never be released from prison when he was sentenced for the abduction and murder and of April, at Mold Crown Court in 2013.

April, who suffered from cerebral palsy, also lived in Machynlleth and was last seen getting into Bridger’s car. He denied her murder, later claiming that he had accidentally killed her in a car accident, and could not remember disposing of her body due to alcohol and panic.

April’s body was never recovered, although fragments of bone were found in the fireplace of Bridger’s cottage which was later demolished.

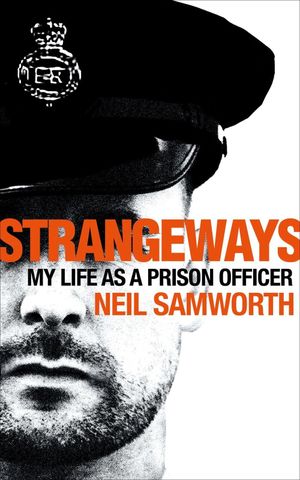

In his memoirs, Strangeways: My Life as a Prison Officer, Mr Samworth lays bare the toll that working with some of Britain’s most notorious prisoners has had on his life.

He says a senior nurse who worked with him on the health care unit was reduced to tears when she read about the effects working with Bridger had on Mr Samworth.

“Every interaction between Bridger and ourselves, with other prisoners, with people coming in and seeing him for the first time, it was the same,” says Mr Samworth.

“People have said ‘I hate him’, ‘I detest him’.

“When one of my own nurses read the book, she cried after reading it, she didn’t realise how working with people like that had affected me.

“I never had any training in dealing with the mentally unhealthy, or paedophiles or kiddy killers, or anything like that.”

He says Bridger was in a completely different category to other prisoners, even other sex offenders.

“If you work on the vulnerable prisoners unit, with the sex offenders and rapists, you will not usually know what they have done, and you will not need to know,” he says.

“But with Bridger, it’s not what he’s done, it’s what he’s like. All the time he was in there, it was 'me, me', he is a complete narcissist. Any conversation and any question you ask him he will turn it around to be about himself.

“He was whining he’d never see his dog again and he’d probably be in prison when his parents died.”

Eventually, the stress of having to deal with people like Bridger, the effects of drugs in prisons – particularly the former ‘legal highs’ such as spice which remain freely available in jails – and staff shortages began having a major impact on his health.

“I wasn’t in a great place physically or mentally,” says Mr Samworth, 55, who lives in Manchester with his partner Amy and 11-year-old daughter.

Last year he retired on health grounds, after suffering post-traumatic stress disorder, and he says finally being able to speak out about what he has had to deal with has been a huge relief.

“For the past week, I have finally been able to walk around with a smile on my face,” he says.

He believes for people such as Bridger, the death penalty might be the best answer.