Home schooling: Why are parents choosing to educate their children?

About 60,000 children in the UK are home-schooled – but just what attracts parents to providing their children’s education, and what are the drawbacks?

On a Monday morning it’s a familiar sight to see uniform-clad children heading to school.

Yet it’s not the same routine for all children.

According to Shropshire Council and Telford & Wrekin Council there are currently 655 children registered as being home schooled in the region. Three years ago during the 2014/15 academic year this figure was 413.

In February England’s children’s commissioner Anne Longfield compiled a report which estimates there were 60,000 home-schooled pupils at any one time in 2018.

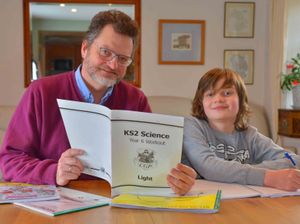

Dylan Harrison found himself in a situation at the start of this academic year where he was home schooling his 11-year-old son Maxim.

Max was diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder and mild attention deficit hyperactivity disorder when he was six.

He was a pupil at Castle House School independent prep school in Newport, but after a series of incidents, Dylan was asked to withdraw his son from the school, although after a tribunal the school issued an apology.

“Max was so traumatised that he became depressed,” said Dylan. “He had what he called ‘the feeling’, which was basically the feeling that he didn’t want to be alive anymore. He was 10 years old at the time.”

Max had lost his routine and his friends overnight and was sent to a mainstream primary school.

“They tried really hard, but they didn’t know him from Adam,” says Dylan.

“It was just horrific, to have a child who was always happy, bouncy, mischievous and healthy child to him just lying on the sofa with a sick bucket just saying ‘I’m not leaving the house’, within a few months was devastating.

“The school became a battleground. He didn’t want to go. We couldn’t get him there. I’m trying to go to work, my wife is trying to go to work and we would be spending two or three hours in the morning trying to get him out the house.”

Dylan is a social worker of 25 years, and has previously worked in mental health services, but he said none of that was able to prepare him for what his son was going through.

“I couldn’t get my head around the fact he was suicidally depressed,” says Dylan. “He was telling us in a very frightened and embarrassed manner that he didn’t want to be on the earth any more. It’s your worst nightmare as a parent really. You feel alone with it, but you’ve to just cope.”

Dylan and his wife Joanna, a lecturer at Wolverhampton University, decided to slow things down decided to take Max out of school.

“We just thought ‘we need to stop everything and take stock’, so we made the decision to home school,” says Dylan.

The process of withdrawing Max from school was relatively easy – although there was no financial support.

“Anybody could do it. You just have to be able to show you are providing an education if anyone ever asks,” he says. “There are so many children, particularly with autism, that are not in mainstream education. Parents give up their lives and put their lives on hold for years to educate their children at home.”

One of the places that provides creative and outdoor learning for those parents who home educate is Wrekin Forest School which is run by former primary school teacher Judy Ellis.

Judy says that she has seen a big rise in home education for a variety of reasons.

“There are some who it it through choice and there are also those who feel forced out of the system,” says Judy as she stands surrounded by children running around and playing on swings and zip wires.

“ Maybe those with ADHD or autism are being forced out because they are not able to meet the criteria that the current systems are pushing for. Unfortunately there is an increasing number of those who are square pegs in round holes because the creative elements are being pushed out.”

Judy takes some of her outdoor learning, which she says ticks off up to 80 per cent of the curriculum for early years and Key Stage One. But as contracts end this element of learning is being cut because of financial pressures on headteachers.

“One school is in the red this year and the headteacher feels that the only thing she can cut is this,” says Judy. “There’s a lot of children there who will not be ticking the academic boxes in the classrooms, but outside with me were achieving.

“Some of the guys that come from home education are really struggling to ever be calm. But here they can rest, watch a fire flickering, listen to the birds and it calms them down. It is very enhancing for someone’s mental well being.”

Home schooling does come with it’s downsides. Judy says the decision to home school for parents is a big and difficult one to make.

“For some it’s a massive sacrifice,” she says. “One parent having to give up a job to have a child on their home. That is a huge commitment. The parents then have to pay to come to places like here and to sit exams. They aren’t getting anything for free. If you want to sit GCSEs then you have to pay for them. You lose an income and have a lot more to pay for – it’s not a decision most parents take lightly.”

Dylan said he and his family also felt some of those impacts while Max was at home.

“The big drawback is isolation, both for the child and the parent,” says Dylan. “It reduces your standard of living dramatically.

“When 25 per cent of the household income is gone it can be a huge thing and does impact on our other two children Elizabeth and Nicholas.

“I have met people who are highly qualified who have had really good jobs who just aren’t working now and haven’t for years and have effectively given up their careers completely. It wasn’t something neither me or my wife were prepared to do, so we made the decision we would have to work around it with reduced hours.”

Max’s confidence has grown, and he is now able to return to school – but faces a fresh challenge as he prepares to start secondary school in September.