Meet the astronomer who sent a little bit of Shropshire to Mars

When NASA’s rover Perseverance launched into space from Cape Canaveral in July 2020, it took a tiny piece of Shropshire with it.

As it settled on Mars seven months later, and began its explorations of the Red Planet, the name of Whittington was buried deep in one of its microchips. The village’s name is still there now as Perseverance scuttles around, drills into rocks, gets blasted by tornadoes of dust and continues to seek Martian life.

The man responsible for Whittington’s presence 30 million miles from Earth is Pete Williamson, who has lived in Shropshire for the past 32 years. Pete responded to NASA’s open invitation to personalise the Mars probe with reminders of home, adding the name of his north-west Shropshire village as a way of getting fellow residents energised by his passion for space.

“I was sitting at home, and I thought, ‘I’m sitting here doing what I’m doing but nobody round here really knows what I do,” Pete says.

"I thought I’d get the village involved. I put a post up [on the Nextdoor social network] that the village had gone to Mars and away it went. The village is interested now, and I like to see the fact that we’re on Mars.”

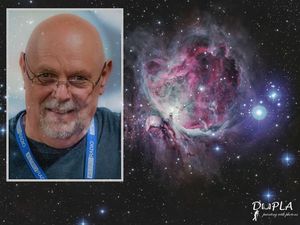

When Pete, aged 65, is “doing what he’s doing”, he is one of the UK’s leading freelance astronomers, regularly in contact with major space agencies across the world. He works mostly for Cardiff University, accessing data sent from Perseverance to NASA’s labs and processing spectacular images captured by the probe.

His photographic posts on Nextdoor, which he titles 'Whittington on Mars' or 'Whittington in Space', are greeted with reliable awe from a dedicated following. Some photos depict breathtaking rock formations and craters; dramatic and barren landscapes. Others show dazzling nightscapes and incredible nebulae captured above familiar landmarks in Shropshire or North Wales.

One Nextdoor commenter wrote: “I might not have got to be an astronaut but you have made me a very happy earthbound person.”

It’s all in a day’s work for Pete, who is both a researcher and an educator on everything related to space, and a talented photographer.

Before Covid intervened, he used to give more than 200 talks a year to schools and associations, either introducing the world of astronomy to young students, or relaying the latest developments to captivated crowds. He presents a programme about astronomy on BBC Radio Shropshire, manages an astronomy-themed radio station from his home and organises, with his daughter Sarah, the Solarsphere Astronomical & Music Festival, in Builth Wells.

He has remote access to telescopes located across the globe – South Africa, Australia, Hawaii – with which he can peer across our galaxy and beyond. He is a true space explorer, without ever leaving the Whittington home that he shares with his wife Sybil.

“It’s a very surreal job,” he says. “One minute I am working with data live from the surface of Mars, the next wandering round an ancient castle for a break. Or at night you log on and you're looking on Mars. You can see the surface. Then you step outside, look up, and see that little dot and think ‘I've been working on there’.”

Pete first fell in love with astronomy as a 12-year-old and built himself his first crude telescope a year later. Although a career in music meant he could pursue astronomy only as a hobby for much of his adult life – he was in several successful bands – an injury to tendons in his left arm meant he could no longer play bass guitar. Music’s loss became astronomy’s gain.

By that point, he had moved to Whittington and founded what became the Shropshire Astronomical Society, with help from Sir Patrick Moore. He had also created an early astronomy bulletin board, with Queen’s Brian May among the first subscribers. Pete is still in touch with May, who is a keen astronomer, but it’s not Pete’s only brush with celebrity. He also became friends with Neil Armstrong, a hero to all stargazers.

“I was 13 when they landed on the moon,” Pete says. “We look at the pictures now and they’re hazy and blurred and you can hardly see anything. But at the time it was ‘Wow! That’s the moon! He’s on the moon!’”

Pete says the “wow factor” is crucial to get young people involved in science, and space offers hundreds of fantastic facts and staggering stats. He demonstrates one on the table in the Whittington Castle tea room, where we meet. Placing one finger next to another, he says: “If I put the Earth there and Pluto there where would the nearest star be apart from the sun?” I tell him I don’t know.

“New York. That's the scale we're talking.”

He says he loves watching young people discover space for the first time.

“When I first go into schools, or if I've got kids at a telescope, I show them the moon,” Pete says.

“You can't miss it. But to see it through a telescope they look at it and they see craters and mountains. They realise it’s real, it's here. And then maybe Saturn with its rings around it.”

Like many astronomers, Pete is tormented more than anything these days by light pollution and talks with dismay about the proliferation of residential security lights, plus intrusive street lighting, whose ambient glow makes stargazing much more difficult.

“When we first moved here 30-odd years ago, it was very rural,” he says.

“You’d go and stand in the garden and you’d never see a light. But now you just step in the garden and it’s like living in the middle of a city.”

He has campaigned to the council to install lights from which there is less leakage, but says he hasn’t gained much traction. He also points out that it’s not just astronomers whose lives are adversely affected by the lights.

“If you’ve got something lit up all the time, the wildlife doesn’t know if it’s night or day and tends to stay away,” Pete says.

“It affects the ecology. Those animals move out of the area and other animals will move in. It changes things.”

Pete is officially retiring this year but shows few signs of giving up any of his numerous roles. After an enforced two-year break, tickets are selling fast for the 2022 Solarsphere Festival, while Pete is lining up more guests for the radio and arranging new talks and lectures for recent space converts.

And Pete himself remains as fascinated by everything as ever.

“It’s Harry Potter stuff,” he says. “To be able to operate all this stuff remotely, as far as Mars, or going round Jupiter. When I was a kid, did I ever imagine I’d be able to do that? No. We hadn’t even been into space.

"It’s a surreal experience. I never undervalue what I’m doing.”

Peter's five top tips for a young astronomer

Learn the night sky - where and when different constellations are up

Decide whether you need a telescope. Pete recommends binoculars to start with.

Join an astronomy club and test their telescopes

Decide what you want to look at and learn which telescope is best

Assess your surroundings and tailor your stargazing to your rural or city setting

Pete's top four local places to stargaze

Dark Sky Discovery Sites, Carding Mill

Long Mynd trails

Alwyn Reservoir, Corwen, North Wales

Horseshoe Pass, outside Llangollen