Football Manager 2019: Meet the Shropshire brothers who created the best-selling game

As Football Manager 2019 is released we speak to the siblings about how they created the game, and how a goat on a Shropshire smallholding nearly stopped it ever getting made.

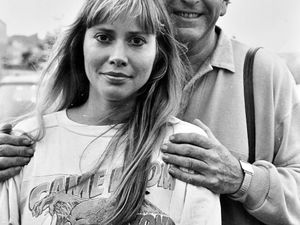

The Collyer brothers may be responsible for hours of lost time over the coming days and months as the highly addictive Football Manager 2019 hits the shelves today.

And it is all thanks to one Shropshire duo. After all, they are the inventors of the game itself.

Players spend hours tweaking tactics, making signings, challenging for titles. The game itself assesses how addicted you are to it. It has even been cited in divorce proceedings.

Co-creator Paul Collyer recalls a tale of one young man who had invited his new girlfriend’s parents round for Sunday dinner, but because he couldn’t put the game down he never sat down for the food. Unsurprisingly, the relationship didn’t last.

Such matters could hardly have been imagined when Paul and brother Oliver created the programme for the game as teenagers in Shropshire, in an effort to overcome their rural home’s scratchy radio signal.

The Collyers’ childhood was very familiar to people who grew up in the county – including hayfever, cow muck and having a “local” shop so far away that nipping for milk took considerable advance planning.

The London cafe in which they recount the tale feels a million miles from the rural smallholding at Strefford near Church Stretton on which the grew up, with a cow, sheep, ducks, chickens and a goat for company.

Indeed that goat could have stopped the game ever being created as its voracious appetite saw bits of computer equipment disappear down its throat.

“Fortunately he didn’t eat the game’s code,” laughs older sibling Paul.

When they weren’t riding horses or lugging around barrows full of manure, the brothers obsessed over football and computer gaming.

The Everton fans would listen to the radio for scores and commentary, and in 1983 Paul created an early precursor to the brother's first game, Championship Manager, on a BBC Micro computer.

“We didn’t even have Teletext back then as we had such a terrible TV signal,” he says wistfully.

“I would listen to the radio to get the results, then type them in to the computer and it would update the league tables on the screen. That was my first venture into football programming.”

Oliver and Paul were pupils at Church Stretton School, and in the summer would play football with friends – although they weren’t quite cut out for the professional game.

“I was terrible, says Paul, who turned out for local boys team The Magpies.

“We’d end up with a minus goal difference of 150 at the end of the season.”

They did not come from a footballing family. Even persuading their dad to take them to a vital Shrewsbury match couldn’t kindle an interest.

“He was so enthusiastic that he fell asleep when Shrewsbury stayed up on the last day of the season,” smiles Oliver. “They either drew or won, and it was enough to keep Town up. Dad was asleep snoring.”

Creating the beautiful game

They had time on their hands, particularly in the winter months, allowing them to fiddle with their computer in the evenings.

The brothers played early football management simulators recommended by gaming magazines, but spotted their limitations.

They were learning code from games they played at school and specialist publications, and in 1985 began to turn their code into a game, even if they were “winging it”.

Paul, now 49, says: “Where we lived was very cut off, you couldn’t walk to the shop, and even biking it was a bit far. The only hanging out after school was the boys from Strefford in the summer when it was light enough to play football. Beyond that there wasn’t really much to do.

“If we’d been out smoking fags and riding BMXs in the town nothing would have happened. The circumstances were very open to that kind of obsession.

“We never sat down and said let’s make a football management game. We just kind of did it. Brothers are like that sometimes, you don’t analyse things you just sit and do it. It was only really for us.”

Soon Oliver, 46, began differentiating between players’ qualities – even if their attributes were limited to “skill” and “pace”.

Friends would visit on weekends, and for years only this select circle of Shropshire school pals played the game. But after Oliver went to study mathematics at university in Leeds, things changed.

“I quit the course after the first year and came back to Shropshire,” says Oliver.

“That summer we polished the game and we thought we’d actually try and do something with it.

“Our friends were telling us it was a really good game and we’d spend hours on it, having fun.

“We thought why not send it off to publishers and see what happens? What’s the worst that could happen? They could say no–which most of them did to be fair.”

Some publishers disliked the lack of graphics and the radio-style commentary, derived from the game’s origins tuning in to a scratchy signal, but one – Domark – offered them a deal.

“Looking back it was a pretty awful publishing deal, ,but at the time we thought it was amazing they were giving us any money,” Oliver says.

“We did take it to a lawyer, but he was like the village lawyer. Suddenly he’s got this contract from a publisher in London. He said yeah, the terms are ok, but basically he hadn’t got a clue – we don’t blame him for that.”

The game sold 20,000 copies, and the brothers started development company Sports Interactive.

The follow-up games CM 93/94 and CM Italia, incorporating real, painstakingly typed-in data from the Rothmans Football Yearbook, sold 90,000.

With no family commitments, and enough money to keep them out of regular employment, the brothers created new versions alongside publisher Eidos, before taking their skills and code to Sports Interactive to create the now famous Football Manager series alongside Sonic The Hedgehog developer Sega.

Annual releases of the game now sell millions of copies globally. Some gamers claim to dress up in suits for their own cup final day. A picture circulated on Twitter of a man sat on a step ladder to recreate the sensation of being sent to the stands for a game.

“There was someone who set fire to a waste bin to simulate an away match at Galatasaray in the Turkish cup,” Oliver laughs.

“We love hearing these stories,” Paul adds, beaming.

The brothers now struggle to enjoy playing the game though. Paul, who works on the match engine, is “self banned” because he spots too many things he wants to change.

He does, however, recall his favourite ever game, dragging unfancied Burnley from the Division Three doldrums to top-tier glory on the game’s 93/94 incarnation.

“I remember being bottom of the division after 10 games. I couldn’t get a win or buy a goal so I set the team up to be really negative to get a bunch of draws,” he says, wistfully.

“We finished mid table, got promoted the next season and I got them all the way to the top division.

“It’s funny when you look back on playing the game like that. You start to understand why real managers act the way they do. I was stubbornly determined to prove myself right, and it’s just like that in real life.”

The formula capitalises on every football fan’s belief that they can do better than their team’s manager.

The game continues to change, even adapting to political events like Brexit.

Oliver now works on the touch and hand-held versions of the game. He said: “Things like VAR and Brexit we simulate in the most obvious way that fits the game. They are almost perfect changes for us we can make every year.”

The brothers still go home now and again to visit family and friends.

“When I go back there now I adore the nature,” Paul added. “I want to go for a bike ride, run, or walk and actually enjoy it. When I was there I didn’t appreciate it as much because you’re used to it – but now I really enjoy it. It’s nice to get out of the city.”

Football Manager 2019 is available in shops from today.