The cricket-mad Shropshire lad who helped found AC Milan

The famous red and black stripes have been worn by legends like Paolo Maldini, Ronaldinho and Kaka.

But AC Milan, one of football’s most decorated clubs, had humble beginnings involving a Shropshire man.

When Alfred Ormond Edwards and a cohort of fellow Englishmen and Italians set up Milan Football and Cricket Club in the city’s swanky Hotel Du Nord et des Anglais 120 years ago, little did they know they were starting an institution that would entertain millions, create superstars and go on to become champions of Europe seven times.

Born on October 12, 1850, in Skyborry, near Knighton, on the border of Shropshire and Powys, Edwards was the seventh child of Charles and Theadosia.

He was an engineer by trade and moved to London, where he married Eliza Fanny Oriel when he was 28.

Edwards later moved to Italy, where he was a high flier in business and society, serving as British vice-consul. It was there, in 1899, he came across football-mad Herbert Kilpin from Nottingham.

'Italians never took to cricket'

Robert Nieri, an Italian football historian, said of Edwards: “He was a cricket man but Kilpin persuaded him to get involved in football. The cricket side of the club carried on for a little while but was done away with after about two or three years. The Italians never took to cricket.

“I’m not sure how they both met. Kilpin was a textile worker and was very working class. He was the son of a butcher. So quite different to Edwards. Kilpin lived in Turin for seven years or so but then moved to Milan. At some point he came across Edwards and between them they came up with the concept for the club.

“The club was officially formed at the poshest hotel in Milan and had about 40 members at the start.”

The bald-headed and moustachioed Edwards became the club’s first ever chairman, though he was not as obsessed with the game as Kilpin, who would go on to be player-manager.

Kilpin’s story is the stuff of legend. He left his own wedding to play a match against Grasshoppers Zurich in Genoa, returning to his wife with a broken nose that night.

He was also said to dig a hole behind the goal to put a bottle of whisky into, which he would swig to console himself if he missed an easy chance.

It’s difficult to imagine Shevchenko sneaking a tipple in the goalmouth at Istanbul, ready to drown his sorrows after Jerzy Dudek saved his penalty in the 2005 Champions League Final.

Influence

The Shropshire lad’s starring role, however, proved to be off the field, where he used his connections in the business world to generate a huge following for the club.

It is also believed he was influential in getting the Pirelli family, the tyre giants, involved in the club. Two of the owner’s sons played for the team.

The club became a success very quickly, winning its first national title just two years after forming and added another two during Edwards’ tenure.

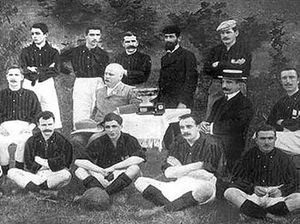

Robert added: “Edwards was a big part of the club. There are various pictures of him and one with him with their first trophy, sitting in the middle of all the players.”

“They started playing games and were mainly made up of ex-pats and students. The Pirelli boys played, and were probably introduced to the team by Edwards because of his contacts as a business person.

“Edwards was fairly old when they got together to form the team. He was an engineer by trade before going on to become a business person. He was of a higher social standing and he was able to help build a continuity of support in the city.”

Arrival of Inter

He stayed on as president for 10 years, before leaving in 1909 to return to England. It came shortly after the forming of Inter Milan.

Edwards and Kilpin were indirectly involved in how Inter Milan came about, after an internal disagreement surrounding the signing of foreign players.

Robert added: “They had a lot of Swiss players as well as English people involved. Some of them rebelled and made the new club called Internazionale, meaning international so they could welcome players from any country.”

After football, Edwards lived in Bridgnorth at Bella Vista with Eliza, and helped Belgian refugees settle during the First World War. He died aged 72 in 1929 and was buried in the town’s municipal cemetery, where his grave still lies. But his legacy will live on forever.

Indeed, it is not the only British connection to Italian football.

Juventus, the most successful club in Italy domestically, wear black and white stripes thanks to one of their players, an Englishman called John Savage, who got a Notts County-supporting friend to send strips over to replace their faded pink kits.

Another player who spent time in Shropshire, Gerry Hitchens, scored huge success in Italy.

The Staffordshire-born striker played for Inter, Torino, Atalanta and Cagliari as well as for the English national team. A far cry from his early beginnings turning out for Highley Miners Welfare.

Edwards’ partner Kilpin has been remembered in style years after his death.

Robert wrote the book Lord of Milan and helped produce a documentary of the same name, which went on to receive high acclaim at the Milan Film Festival in 2016.

And in his home town of Nottingham, Kilpin has a plaque at his birthplace, a pub and even a bus named after him. Yet in Shropshire, Edwards is barely known of.

Robert said: “I think Shropshire should be very proud of their connection and he should be celebrated.”