Why do people believe in conspiracy theories?

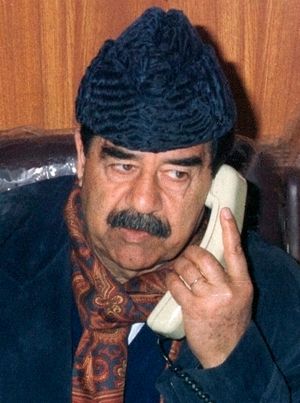

There was a story doing the rounds in the run-up to the 1991 Gulf War that former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein refused to take a call from President George H W Bush, believing that the US leader would be able to assassinate him by telephone.

It was reported at the time as an example of the Iraqi dictator's mad paranoia. Yet almost 30 years on, it seems there are millions of people around the world who are convinced that the coronavirus could be spread through mobile telephone masts.

Conspiracy theories about the 5G mobile phone network have been circulating on the internet for weeks, resulting in nine mobile phone masts across the West Midlands being vandalised, some of them serving NHS hospitals.

Claims that 5G is linked to the disease have been widely discredited by experts from the NHS, the World Health Organisation and leading scientists, who describe such theories as "both a physical and a biological impossibility". Prof Stephen Powis, medical director for NHS England, described the theory as "absolute and utter rubbish.”

But despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary, there remains a sizeable section of the population that is willing to believe such conspiracy theories.

Of course this is nothing new. From claims that Neil Armstrong's moon landing never happened, to reports of Elvis Presley still being alive, conspiracy theories have become part and parcel of modern life. A 2017 survey found that 61 per cent of Americans believe that Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone in the assassination of John F Kennedy.

The spread of these theories has been turbocharged by the introduction of the worldwide web, where people are free to spread all manner of misinformation online, with little in the way of consequences. Such obvious untruths as Hillary Clinton masterminding a world child-trafficking ring from a pizza restaurant in Washington, and George W Bush being behind the attack on the Twin Towers, have all gained traction on the internet, and it seems some people are only too willing to believe them.

Prof Joe Uscinski, author of American Conspiracy Theories, says most people are more susceptible to conspiracy theories than we care to think.

"Everybody believes in at least one and probably a few," he says. "And the reason is simple: there is an infinite number of conspiracy theories out there. If we were to poll on all of them, everybody is going to check a few boxes."

Research carried out by Cambridge in 2015 found most Britons ticked a box when presented with a list of just five theories. These ranged from the existence of a secret group controlling world events, to contact with aliens.

It seems it would also be wrong to assume that the average conspiracy theorist is a full-time obsessive trying to save the world from the bedroom of council flat.

Prof Chris French, a psychologist at Goldsmith's College, University of London, says the demographic date suggests a willingness to believe such theories cuts across age, sex and social class.

And while many of these theories are politically motivated, they are not the exclusive preserve of any position on the political spectrum.

Prof Uscinski says research in the US has shown that belief in conspiracy theories are pretty evenly divided between the left and the right.

"People who believe that Bush blew up the Twin Towers were mostly Democrats, people who thought that Obama faked his own birth certificate were mostly Republicans, but it was about even numbers within each party," he says.

More than half of Britons say they viewed false information about 5G technology during the third week of the lockdown, while other fake news related to Covid-19 appeared to be on the decrease.

Ofcom has asked a group of approximately 2,000 people about their media consumption and attitudes each week since lockdown started.

Exposure to earlier falsehoods, such as the benefits of gargling with salt water or drinking more lemon juice to combat coronavirus, has fallen each week since the survey started, but 5G theories went from zero in weeks one and two to 50 per cent in week three.

Prof French says humans are conditioned to spot patterns and regularities, but sometimes we can be prone to overplaying those.

"We think we see meaning and significance when it isn't really there," he says.

"We also assume that when something happens, it happens because someone or something made it happen for a reason."

In other words, people explain coincidences around major news stories by making up stories to fit the facts, often involving 'goodies' and 'baddies', reflecting their own personal likes and dislikes.

Prof Larry Bartels, of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, says people also have a tendency to look to Government for explanations for matters it has no control over whatsoever. One example he looked at was a series of shark attacks off the cost of New Jersey in 1916, the story of which formed the basis of the movie Jaws

"We found that there was a pretty significant downturn in support for President Wilson in the areas that had been most heavily affected by the shark attacks," he says.

Prof Karen Douglas of Kent University believes there are three main motives for people being drawn to conspiracy theories: the desire for understanding and certainty; the desire for control and security; and the wish to maintain a positive self-image. In other words, people seek explanations for things they don't understand, come up with a theory that reassures them of their view of the world, and stick with it because they are too emotionally invested to admit it may be wrong.

David Ludden, of Psychology Today, says most of us harbour false beliefs of some kind.

"For example, if you believe Sydney is the capital of Australia, you’re the victim of a false belief," he says. "But once you’re confronted with the fact Canberra is the capital of Australia, you’ll readily change your mind. After all, you were simply misinformed, and you’re not emotionally invested in it.

"Conspiracy theories are also false beliefs. But people who believe in them have a vested interest in maintaining them. First, they’ve put some effort into understanding the conspiracy-theory explanation for the event, whether by reading books, going to web sites, or watching TV programs that support their beliefs."

Ludden says research shows that it is people who feel socially marginalised who are most likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

"We all have a desire to maintain a positive self-image, which usually comes from the roles we play in life, our jobs and our relationships with family and friends," he says.

"But say Uncle Joe is on disability and hasn’t worked in years. He feels socially excluded. However, he does have plenty of time to surf the internet for information about conspiracy theories, and he can chat online with others who hold similar beliefs. Thus, belief in conspiracy theories gives Uncle Joe a sense of community. Furthermore, his research into conspiracy theories has given him a sense that he is the holder of privileged knowledge."