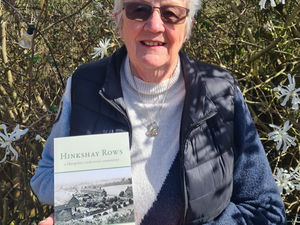

Half a century of Spaghetti Junction's 'magnificent seven miles'

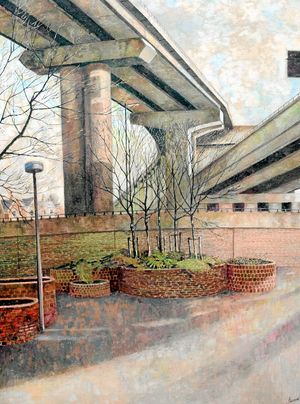

Standing on the pebbled banks where the River Rea meets the River Tame, you can feel the gentle vibrations in the giant concrete stilts supporting the road above.

The Canada geese are unfazed by the distant rumble. The occupants of a passing narrowboat survey the scene around them, the wild flowers poking out of the ground like purple paintbrushes providing a sharp contrast to the yellowing concrete.

This is Spaghetti Junction of course, which today marks its 50th birthday.

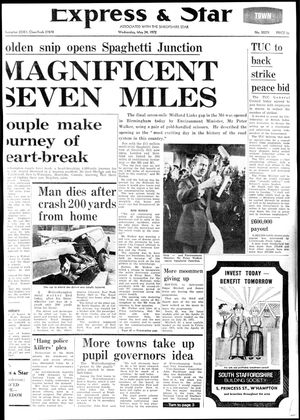

When Environment Minister Peter Walker opened the new intersection on May 24, 1972, he described it as the "most exciting day in the history of the road system in this country."

This newspaper was more succinct. "Magnificent Seven Miles" was the headline. But either way, the excitement surrounding the new structure was immense.

Immediately it was besieged by drivers eager to experience an exciting new chapter in motoring history, while coach operators offered sightseeing tours at 65p a head.

West Midlands mayor Andy Street was just eight years old.

"My grandad used to take me on a Sunday afternoon to look at the building, it was exciting," he recalls.

“It was, sort of, modern and futuristic. And it’s provided a brilliant service for 50 years."

Formally known as the Gravelly Hill Interchange, this newspaper had already dubbed it Spaghetti Junction before it had even opened.

And Magnificent Seven Miles was something of an understatement. The road junction actually serves 18 different routes, and you would have to drive 73 miles to travel the entire junction – even though it covers less than a mile of the M6.

Work began in June, 1968, and was supposed to take three years and cost £8 million. It actually took nearly four years, and cost £10.8m – about £110m in today's money. The opening of the junction was delayed a few months following the collapse of bridges using similar "box girder" construction in Australia and Wales. When the junction was opened it was designed to last 120 years.

In an unusual meeting of old and new forms of transport, the pillars supporting the flyovers across the Birmingham Canal had to be carefully placed to enable a horse-drawn canal boat to pass beneath, without fouling the tow rope. Today it is still popular with narrowboat fans, although the boats are more likely to be diesel rather than horse-powered.

The sandy coloured Salford Turnover Bridge is a beautiful piece of civil engineering, even if it has been marred by the mindlessness of graffiti offenders. At the end of one of the canal tunnels is an opening supported by 13 columns, resembling a Roman collonade.

None of this happened by accident, though. Rather it was the result of a most ingenious engineering solution to the challenges of constructing such a large development in the heart of one of Europe's biggest conurbations.

When the plans were unveiled in the late 1960s, transport minister Stephen Swingler said driving motorways through the built-up areas of the West Midlands would cost £2-3 million a mile, compared to £750,000 in rural areas.

But while threading the route around the edge of the West Midlands would would save money and reduce disruption, it would also mean longer roads and greater journey times.

The solution was to build the road on stilts above existing canals and railway lines, which meant it was possible to create a short, direct route through the urban heartlands without the need for widescale demolition. Today it is easy to forget just how the construction of this vital road junction transformed motoring in Britain.

It meant for the first time it was possible to travel from London to Glasgow along a continuous 300-mile stretch of motorway. In one day, Britain went from having a fragmented network of roads to a seamless motorway network connecting all its great cities.

The story began when Prime Minister Harold Macmillan cut the ribbon on the Preston Bypass in 1958, the first phase of a plan to create a national network of three high speed "motorways".

The Preston Bypass became the M6, eventually extending to Birmingham in the south and Glasgow in the north. A second motorway, the M1, would run from London to Yorkshire, while the M5 would link Birmingham to South Wales.

These roads certainly made journey times quicker, but they were still very regional in their nature, serving specific parts of the UK. Spaghetti Junction brought them all together, transforming the three separate routes into a single integrated network. It meant people could make seamless journeys across the country without ever leaving the motorway.

Actually, there was a little more to it than that. Spaghetti Junction was just one part of the complex Midland Links project to bring the motorways together. But as the final piece in the jigsaw, and with its unique multi-level design – and memorable nickname – the Gravelly Hill Interchange quickly became the standard-bearer for the project.

But even the planners did not realise how crucial it would become to the nation's infrastructure. It was designed to carry 75,000 vehicles a day, and in 1972 the actual figure was just half that. But 220,000 vehicles use the junction every day, and approximately five million tons of freight are carried along it every week.

There was also a darker side to its strategic importance. During the Cold War the Soviet Union was said to have identified it as a target for nuclear attack.

And not everyone was impressed. Birmingham historian Vivian Bird, writing in 1974, referred to Spaghetti Junction as an act of 'plandalism', calling it the "Gravelly Hill earthquake" and a wall that imprisoned the people of Birmingham.

Half a century on, Spaghetti Junction forms part of the cultural fabric of the West Midlands.

The year after it opened, Cliff Richard sped below it on a hovercraft in the film Take Me High, and the vast areas beneath it have become a popular with film makers wanting a gritty, urban setting. The junction is woven into the vestments of the clergy at Birmingham Cathedral, and an overhead view of it featured in the opening credits of the short-lived Midlands soap opera Family Pride. It was also the subject of a painting by West Midland artist Roland Twynam in 1983.

Indeed, food manufacturer Heinz has even produced a limited edition spaghetti tin to mark the occasion, although this may leave a sour taste in the mouth for those still bitter at the way the company closed the 108-year-old HP Sauce factory – a stone's throw from the junction – in 2007.

National Highways customer service director Melanie Clarke says the level of interest that people still show in the junction demonstrates its enduring appeal.

She says: "The structure is a real feat of engineering and it's an iconic part of England's motorway network which, from the moment it first opened, really captured the imagination of the public and motorists."