Ludlow war trophy which survived a scrap drive

At a time of national crisis, Ludlow stuck to its guns. Or gun, to be more accurate.

Not so Bridgnorth, and various other places, which sacrificed their trophies from the Crimean War for another war effort as an appeal went out for scrap metal during the fight against Hitler.

Bridgnorth local historian Clive Gwilt had long suspected that the old cannon, which for generations was a prized display piece in Bridgnorth, had disappeared during the 1939-1945 war, but has now been able to confirm it and narrow down the date.

"I'm doing research on World War Two in Bridgnorth. I was looking through all the old Bridgnorth Journals and I came across the announcement that the cannon was to be taken for scrap metal, which confirms its fate. However some locals still think they remember it," he said.

"Even in my first visitors guide in 1981 I wrote the cannon may have been taken for war efforts."

That newspaper report was on June 6, 1942, and reads: "A familiar sight to many generations of Bridgnorthians, the old cannon on the Castle Walk, is to be used for salvage.

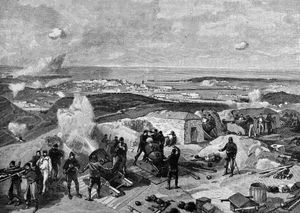

"It was captured at Sebastopol and is to be dismantled next week. It was hoped to have exhibited the cannon in High Street during the present drive but circumstances did not permit."

Old pictures show that the ancient artillery piece had a high vantage point in the grounds of the castle, the muzzle pointing out somewhere in the general direction of the River Severn.

It gave its name to the Cannon Steps running from New Road to the castle grounds, one of several flights of steps linking Low Town to High Town.

By the 1920s plainly the wooden parts were in need of repair or replacement as among Clive's historical memorabilia is a quote dated June 30, 1927, from Messrs Horne & Meredith builders and contractors of Whitburn Street, Bridgnorth, for work on the relic.

Sent to Mr J T Foxall, who was perhaps the town clerk or in a similar role, it gave an estimate of £12 "to block up the cannon during operations, take out the ironwork from the horizontal beam and struts, provide new English oak beam and struts and fix same complete using the old ironwork as far as possible".

But why did Bridgnorth give up its cannon, but Ludlow's war trophy remain to this day, in pride of place near the entrance to Ludlow Castle?

The story of Britain's trophy guns from the Crimean War, and in particular that of the Ludlow gun, was researched a few years ago by Roger Bartlett, of University College London, and Roy Payne, of Ludlow History Research Group, and was told in an article by them carried in The Journal of the Historical Association.

With the fall of Sevastopol – that's how it's generally spelt these days – the British and French acquired large numbers of Russian guns. Hundreds were shipped back to Britain and after some debate about what to do with them it was decided to offer them to any towns that wanted them.

Ludlow applied in 1857, so did Leominster and Bridgnorth, but Shrewsbury did not, causing the Shrewsbury Chronicle to wax indignant, write Bartlett and Payne.

Ludlow's gun arrived by goods train in November that year, initially being put in Market Place, but being moved a few months later to near the castle entrance, where it has remained ever since.

The researchers say not everybody was in favour, pointing to an 1860 book by Walter White called All Round The Wrekin who, writing of his visit to Ludlow, said: "The main entrance (to the castle) is... an arched gateway... which gains nothing in picturesque effect by having in front of it one of those stupid trophies from Sebastopol – a Russian gun. It seems to me a mistake to have distributed those ugly things over the land; eyesores in the quiet streets of country towns..."

Bartlett and Payne write that the Crimean trophy guns remained in place throughout the 19th century, and after the Great War many British towns and cities were similarly offered captured German ordnance.

"Ludlow acquired a German field gun, which was placed like its Russian predecessor in Castle Walk.

"In the Second World War a great many Crimean guns fell victim to the Government's drive to collect scrap metal.

"The Crimean trophies at Bath, Cheltenham, Derby, Glasgow, Lichfield, Portsmouth, Wootton Bassett, to name just a few, were lost in this way.

"The same fate befell the prize cannon at Hereford, Leominster, Bridgnorth, and Wrexham. Ludlow also answered the call to contribute scrap for the national salvage effort, but it chose not to sacrifice its Russian cannon."

While Ludlow held on to that relic, it did give up the German gun and other redundant metal items for scrap.

Bartlett and Payne's researches reveal interesting twists in relation to Ludlow's cannon. It is a frigate's cannon which was cast in 1799, so was already over 50 years old by the time of its capture. It was cast at the Alexander Foundry at Petrozavodsk, about 300 miles north of St Petersburg. The foundry at that time was run by an Englishman, Sir Charles Gascoigne.

"Ludlow, along with other British towns and cities, acquired a Russian cannon cast in the 18th century by an expatriate British ironmaster."

One other use for the captured guns should be mentioned. Metal from one of them is traditionally said to have been used for a new medal, awarded for greats act of valour – the Victoria Cross.

The metal is held at the Ministry of Defence depot at Donnington in Telford. It should be added that there have been modern claims that it does not derive from a gun captured in the Crimean War, but from a gun captured in the second Anglo-Chinese war of 1860.