Shrewsbury hero of the ‘Greatest Raid of All’ dies at 97

A Shrewsbury soldier who was the last Commando to take part in the Second World War raid on Saint-Nazaire has died, aged 97.

Commando Bill ‘Tiger’ Watson, from Shrewsbury, was among 611 British soldiers and sailors who, in March 1942, mounted what became known as ‘The Greatest Raid of All’, code-named Operation Chariot, a daring sea-to-land attack on German naval positions in occupied France.

The aim was to destroy the huge, heavily defended dry dock at Saint-Nazaire on the Loire estuary, which was large enough to take the German battleship Tirpitz.

If the dock had remained intact, the Tirpitz could have attacked British merchant ships in the Atlantic.

The dock was too complex to bomb from the air so, in what looked like a madcap mission, a force of Commandos and naval personnel sailed in 18 small military launches 250 miles from Britain to Normandy and up the River Loire to Saint-Nazaire to do the job.

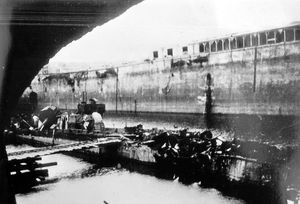

They took with them an elderly destroyer, HMS Campbeltown, which was packed with delayed action explosives and rammed it into the dock gates where it later exploded, putting the dock out of service for the rest of the war.

Twenty-year-old Commando ‘Tiger’ Watson – so-called not for his ferocity but because his smile reminded his commanding officer of the comic-book character Tiger Tim – was one of the first to go ashore that night at Saint-Nazaire.

As a 2nd lieutenant in the Black Watch, he led a five-man protection team assigned to provide covering fire to the British demolition squads.

He had to clear the harbour causeway of the enemy, hold it for the evacuation of the demolition parties and destroy a bridge to prevent German reinforcements arriving.

Following the landing, the Commandos faced hand-to-hand fighting with German troops in the streets of Saint-Nazaire. Watson recalled bullets ricocheting off lamp posts.

He displayed exceptional bravery, at one point turning to his comrades and asking them rhetorically, “Do you want to live forever?” – a comment that he later admitted in embarrassment was “probably due to reading too many action comics”.

When his Tommy gun finally ran out of ammunition, he was felled by a German bullet which passed straight through his left arm. He was later awarded a Military Cross for his bravery during the raid.

With many of the landing craft sunk or set alight on the river, there was little chance of the planned escape home for the British force. One hundred and sixty-nine men who took part in the raid lost their lives, while more than 360 Germans were killed. Watson was taken prisoner with 214 of his comrades.

Under interrogation by the SS following the raid Watson and his fellow Commando Corren Purdon – who later became a Major General – were determined to keep their identities secret for as long as possible.

Both looking considerably younger than their 20 years, they claimed to be boy scouts out on a weekend sailing exercise.

The German translator looked up: “A very long weekend,” he said dryly.

While in prison camp in Germany Watson was allowed to start studying for medicine – and in the last months of the war was sent to work in a German hospital, from where he was liberated by trigger-happy US troops – an experience which, he said, was more frightening than the original raid itself.

Returning home, Watson qualified as a doctor and finally settled as a GP in Shrewsbury. In 1970 he was sitting at the breakfast table with his wife and children when he saw a headline that shocked him: “A million people die of starvation and disease in Biafra”. In his memoirs, he recalls a child’s voice piping up, “Why don’t you go and help them, Daddy?”

For Watson that marked the beginning of many years working as a doctor with humanitarian and relief agencies. His wife Wyn, also a doctor, was able to manage his general practice while he was abroad.

He served with Oxfam in Ethiopia during the famine of 1973, and he and Wyn treated leprosy sufferers for Lepra in Malawi, as well as working in Somalia, Afghanistan, Nepal and Sierra Leone.

In Ethiopia Watson remembered being presented to the then-Emperor, Haile Selassie, who had come to inspect the relief work: “All the beggars were cleared from the streets and the trees were whitewashed for the occasion,” he said.

Watson was a keen supporter of the charity WaterAid. In 1999 he attended the inauguration of two wells in Ghana, which were funded by donations to WaterAid in memory of the Raid on Saint-Nazaire.

Watson was made an MBE in 2002 for his services to Shrewsbury’s Severn Hospice, of which he was a founding member.

He attended memorial services at Saint-Nazaire for many years and was a committee member of the Saint-Nazaire Society.

Wyn, his wife of 68 years, died in November at the age of 95. The couple are survived by four children and nine grandchildren.