'Sleeping driver' mystery of Shropshire's worst rail crash

Eighteen dead at Shrewsbury. Somebody was to blame. They blamed it on the train driver.

He had nodded off, they said.

But had he? The findings of the official report into Shropshire's worst railway disaster were bitterly disputed by men on the footplate. They said it was simply impossible for a driver to fall asleep and put forward an alternative theory that the brakes had failed.

It was 110 years ago that awful screams rent the air at Shrewsbury as the mangled wreck of a derailed train came to rest just short of the town's railway station soon after 2am on Tuesday, October 15, 1907.

As well as the death toll of 18, 30 people were seriously injured, and another 31 less seriously. Four of the dead were from Shrewsbury, three of them being postal workers, as the ill-fated train was a mail train which also carried passengers.

What had gone wrong was immediately apparent through the testimony of witnesses on the train, railway workers, and residents who had heard the express thundering along the line moments before the tragedy.

It was going far too fast as it approached Shrewsbury railway station and jumped the tracks.

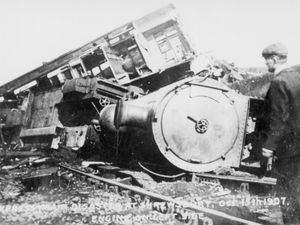

The disaster was a sensation which made national headlines and was covered photographically by postcard makers.

The official report of Lieutenant Colonel H.A. Yorke, on behalf of the Board of Trade, pinned blame firmly on the engine driver, Samuel Martin, of Crewe, who was among the fatalities.

On that fatal run between Crewe and Shrewsbury he may well have been tired and sleepy, he said.

The upshot was that approaching Shrewsbury, sleep overcame him. He passed Harlescott crossing and Crewe Bank without knowing it, and did not see the signals at danger, and on the downward gradient coming in to Shrewsbury the train picked up speed rapidly.

By the time he had woken, or been woken by the fireman, Frederick Fletcher - he too died - he was past Crewe Bank signal box and travelling so fast that despite applying the brake with full force and reversing the engine it was too late.

As for why the fireman did not wake Martin, Lt Col Yorke said that he too was possibly asleep, or perhaps had been too busy to notice.

"Colonel Yorke says he does not suppose that anyone who has had any experience on the footplate will deny the possibility of such a thing happening, and, reviewing all circumstances, he is of opinion that the theory which he propounds is the most probable explanation of the accident," said the Wellington Journal & Shrewsbury News in its report of his findings.

In this, Colonel Yorke was wrong. His conclusions were met with disbelief, resentment and anger among men on the footplate.

A mass meeting was held of engine drivers and firemen at the Lyceum Theatre, Crewe, a few days later protesting at his assumptions, and calling for "practical railwaymen" to conduct accident inquiries in future.

A protest resolution was moved by one C.W. Shipley of York who said he had not yet met a railwayman who believed the report, nor a man who believed it possible for a fireman on any express to have an opportunity of going to sleep on a footplate.

Albert Fox, general secretary of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen, said it was evidently much easier for Board of Trade inspectors to say that a driver failed than that the brake failed.

There was evidence that the engine was reversed, and no driver reversed his engine until his brakes failed, he said.

The same point was made in a resolution from the Liverpool branch of the society. It refuted the finding that the driver and fireman could have been asleep and called for the stigma to be removed from footplate men. The fact that the engine was reversed showed that Martin was fully aware that the brake was not working, it said.

The train was the North and West Express from Crewe. It jumped the track on a curved section just short of Shrewsbury station on the Castle Foregate side of the town.

The locomotive came to a dead stop within only about 100 yards from the point of derailment – less than half of the length of the entire train – and carriages telescoped into it in a ghastly mangle of confused wreckage.

At the point where it derailed, it should have been going about 10mph as it pulled into Shrewsbury station. Instead it was going somewhere between 40mph and 70mph.

One final mystery. After the crash the Shrewsbury Chronicle anonymously published a five-verse poem about the disaster. This was, according to information on the internet, the first published work by famous Shropshire novelist Mary Webb.

In the past various readers have sent us a poem about the rail crash which is 14 verses and starts “It was on a Tuesday morning, A little after two, A sad calamity o’ertook, The fast express from Crewe" and as far as we are aware was written by George Cresswell, who was an engine driver poet.

Has anybody got a copy of Mary Webb's poem? Or could it be that the poem attributed to George Cresswell is actually the one written by Mary Webb?