Telford-based PDSA's century of helping sick animals

In November 1917, Britain was still a year away from the end of the First World War. The streets of London's ravaged East End had descended into a state of squalor, as three years of bitter warfare coupled with grinding poverty took their toll.

And as millions of families struggled to scratch out a living, their menfolk killed or wounded in the trenches, Maria Dickin became increasingly concerned about the plight of the sick or emaciated animals who nobody seemed to care about. A church minister's daughter who had been doing voluntary social work among some of the poorest families in the capital city, she saw at first hand how animals were suffering in the slums of London, and was shocked.

"I could see suffering animals all over the world without anybody to help them and I thought this sort of thing can't go on," she said.

Some of these were working animals who had helped keep the country going during the dark days of war, others were simply pets who families could not afford to look after. Realising that nobody else was going to come to the aid of these poor creatures, Dickin decided the time had come to do something herself.

On November 17, 1917, she opened the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals, Britain's first charity dedicated to providing free healthcare for animals whose owners could not afford to pay for it. She persuaded a vicar to lend her a 13ft-square basement in crowded Whitechapel to open her first dispensary. She also managed to recruit an experienced animal practitioner who had attended to the pets of royalty.

A hundred years on, the charity which is now based in Telford sees 5,300 animals every day, or 13 every minute. A total of 200 staff are based at its headquarters in Whitechapel Way, Priorslee, which opened in 1989, and are supported by 4,000 volunteers across the country.

Dickin wrote a book, The Cry of the Animal, where she described the scenes that convinced her she had to do something:

"In the streets were many dogs and cats walking on three legs, dragging along a broken or injured limb; others nearly blind with mange; covered with sores; nearly all looking dejected and miserable and searching for food in the gutter.

"The suffering and misery of these poor, uncared-for creatures in our overcrowded areas was a revelation to me. I had no idea it existed and it made me indescribably miserable."

Outside her first dispensary she placed a sign saying: "Bring your sick animals. Don't let them suffer. All animals treated. All treatment free."

To say there was some early scepticism towards the charity would be something of an understatement. The veterinary profession was particularly unsympathetic, saying the poor didn't actually care enough about their animals to take them to a clinic. Some felt they shouldn't be allowed to keep them in their first place.

She replied: "You obviously know nothing about poor people.

"Poor people do not only keep animals as pets but as a means of earning their living, people such as costermongers, hawkers and small roundsmen."

She pointed out that the homes of the poor would be "overrun with vermin if they did not keep a cat," while for many dogs provided security.

The doubters were quickly proved wrong. The first day's patients included a cat with mange, a dog with a broken leg and a limping donkey, and all were treated successfully. The word got around, and the clinic was quickly inundated with animals ranging from from parrots to monkeys.

The charity moved to better premises, and the PDSA was soon treating 100 animals a day.

Within five years, seven dispensaries had opened in and around the London area, treating 70,000 animals a year. But Dickin realised there was a need to reach out beyond London, and in 1923 she designed and equipped her first horse-drawn clinic. Within a few years a fleet of mobile dispensaries became a common sight around the country.

As the donations poured in, Dickin noticed a penniless elderly woman putting her wedding ring in a collection tin, because it was all she had to give. She fished the ring out and handed it back to the woman, making a donation on her behalf instead. While her husband Arnold was a successful accountant, Maria was known to pawn her own jewellery to raise funds. She once cleared out Arnold's wardrobe to stock a jumble sale, claiming he had no need for 30 pairs of trousers.

She opened an "animal hospital" in Ilford, East London, in 1928, which was the largest and most advanced animal treatment centre in Europe. It also operated as a training school for the PDSA's staff. This caused no little irritation among the leadership of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, who were unhappy that many of her staff were not trained vets.

In a letter to the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, Dickin replied: "If you are so concerned about proper treatment of the sick animals of the poor, open your own dispensaries ... Show owners how to care for their animals in sickness and health. Do the same work that we are doing. Instead of spending your energy and time hindering us, spend it dealing with this mass misery."

In 1936, the charity opened a centre in Birmingham.

By the outbreak of the Second World War, the PDSA had five animal hospitals, 71 dispensaries and 11 mobile caravan dispensaries. During the Blitz its rescue squads helped more than 250,000 pets injured or buried in rubble.

But Dickin also wanted to recognise the bravery of thousands of animals serving with the military and civil defence forces. In 1943 she established the Dickin Medal for any animal "displaying conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty whilst serving with the British Commonwealth Armed Forces or civil emergency services."

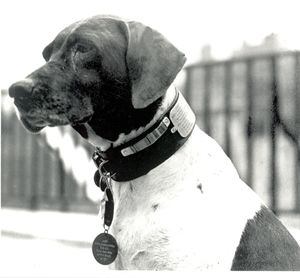

One of the most famous recipients of the Dickin Medal, commonly referred to as the "animals' VC", was Judy, a Pointer who found fame as the only dog to be officially recognised as a Prisoner of War during the Second World War. Judy, who lived from 1936 to 1946, spent her later years attached to the No. 4 Medical Rehabilitation Unit based at RAF Cosford. Initially a ship's mascot serving with the Royal Navy, Judy became invaluable because of her ability to warn the crew of approaching aircraft before they could be heard by the human ear. After the ship HMS Grasshopper was sunk in the Battle of Singapore, she saved the lives of the escaped crew by finding a source of freshwater on the deserted island where they landed.

Judy survived a crocodile attack and, when her crew were taken prisoner by the Japanese, she was smuggled into the camp where she was befriended by Leading Aircraftsman Frank Williams, who persuaded the camp commandant to recognise her as a PoW. She was credited with saving her comrades in both the RAF and the Navy on numerous occasions. The citation on her Dickin Award said it was given “For magnificent courage and endurance in Japanese prison camps which helped maintain morale among her fellow prisoners, and for saving many lives through her intelligence and watchfulness.”

By the 1940s, the PDSA had bases in more than 50 towns and cities across the UK, the nearest with the West Midlands represented by centres in Wolverhampton and Bilston

By this time, the charity was finally recognised by the veterinary profession, and Dickin died on March 1, 1951, at the age of 80.

Today the PDSA operates a network of 48 hospitals, and employs a 1,000-strong veterinary team. Its Telford headquarters was officially opened by the charity's patron, Princess Alexandra, in August 1990.

The charity's work is supported by a national chain of 130 shops and a dedicated army of volunteers, raising £60 million a year to provide veterinary care.

Reflecting on an astonishing century of progress, PDSA director general Jan McLoughlin pays tribute to the vision of Maria Dickin 100 years ago.

"With few resources and precious little support, she set up our first dispensary amid the poverty and chaos of the First World War," says Mrs McLoughlin.

“With an unswerving commitment to helping the most vulnerable animals, and their hard-pressed owners, Maria built upon these humble beginnings to spread the good work further afield, eventually creating a truly national charity."

Mrs McLoughlin says the world has changed beyond recognition since the opening of Maria Dickin's makeshift dispensary in a dingy cellar.

"We have to change too, to ensure our work remains as effective and relevant as possible," she says.

"But our core values remain the same as on Day One. We are here to protect that most precious bond between owners and their beloved pets.”