Kindertransport: The Shropshire school with a remarkable history

Amidst the chaos of the Second World War the sight of evacuees roaming in the relative safety of rural Shropshire was not that unusual.

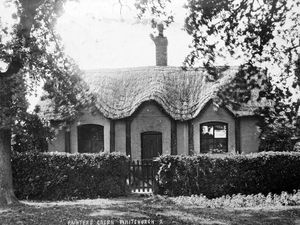

But in Tilley Green near Wem, there something extraordinary was happening. There, a school of German-speaking children could be seen and heard singing in German as they walked through the county’s luscious greenery.

German film and theatre directors, actors, writers and composers were all part of a formidable teaching staff ensconced in Shropshire amidst the bloody global conflict.

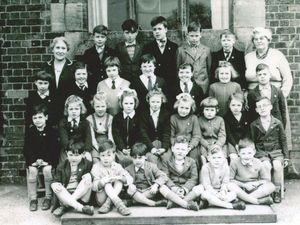

The 100 children in their care had been displaced to Trench Hall as pupils of Bunce Court School, which was run by a Anna Essinger, a German Jew who had been forced to leave her homeland, taking with her a progressive attitude to teaching.

The children had been brought to Britain as part of the Kindertransport, the mass evacuation of 10,000 vulnerable Jewish children from Germany, Austria, Poland and Czechoslovakia as Hitler’s persecution of the Jewish people grew in scale.

And they found a welcome home from home in the north Shropshire countryside. This weekend marks the 80th anniversary of the Kindertransport, rekindling memories of Britain’s most extraordinary act of kindness, which brought scores of children to Shropshire.

The school was founded as New Herrlingen School by Anna and two of her sisters in the German town of Herrlingen in 1926.

It used “progressive educational techniques”, says local historian Alastair Reid, who researched this remarkable story while writing Tilley: The Secret History of a Secret Place at the turn of the millennium.

Corporal punishment was taboo at the school, teachers were called by their first name, and there was no school uniform – principles that were all radical at the time.

Academic study was accompanied by a strong emphasis on music and the arts, as well as physical activity, including daily walks in the woods.

In 1933 Hitler took power in Germany on a wave of anti-Semitism. Jewish teachers were essentially banned from plying their trade in the country and Jewish children were stopped from taking Abitur – the schooling completion exam.

Realising the school was no longer welcome in Germany, Anna and her sister Paula transplanted it to Kent on two buses, one passing through the Netherlands and the other through Switzerland.

They found a new home in an old manor house in Kent called Bunce Court.

In November 1938 after Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, Britain agreed to accept 10,000 predominantly Jewish children as part of the Kindertransport. Bunce Court School took in as many of the refugees as possible.

But after the declaration of War in 1939, large buildings in the south east began to be taken under military control as part of the war effort. Bunce Court had just three days to find a new home. Anna called her friends the Goodbeeyear brothers from Stockport. As it happened, they said, they had recently taken over Trench Hall. The school had a new home.

“The ages of pupils were restricted to between three and 17,” says Alastair, 63.

“They were only allowed a suitcase and weren’t allowed any money or jewellery. Britain was the only country that took on Jewish child refugees after the US refused to break up families.”

The hall was not really fit for purpose as a school. Essinger’s progressive methods of teaching included large sections on practical skills, and on moving to Trench Hall they used their carpentry lessons to make beds, desks and cupboards to allow the school to be used for the children.

“Lessons were taught in English, but lots of the children would still speak German,” says Alastair. “Anna Essinger got an incredible staff together. She had the pick of Jewish teachers,” said Alastair.

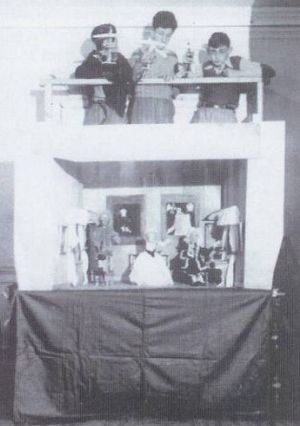

Some of these members of staff included Wilhelm Marckwald an actor and former director of the Deutsches Theater Berlin. Because of restrictions on employment, he became the boiler man for the school and did gardening while his wife worked in the kitchen.

Marckwald immediately formed a theatrical group at the school and began organising plays.

Another teacher was Erich Katz who was later credited to be a driving driving force behind the early music and recorder movements in the United States.

Hanna Bergas was the school’s history teacher and was part of the group of four staff from the school who went to meet the Kindertransports and help the children adjust to their new lives.

In a memoir Hanna wrote “The main thing was to instil in them calm and confidence that the people would be kind to them.”

There were also some high achieving alumni of the school with many becoming professors and leading professionals in their respective fields.

Michael Roemer, now 90, became a film director, producer and writer before becoming a Professor of Art at Yale University in the US, where he still lives.

In a letter to Alastair describing his time at Trench Hall he wrote: “England during the war provided a safe haven for us. It was an unforgettable and very precious period in our lives, and all of us are deeply grateful.”

Alastair says that from the accounts he has, the majority of reports were of “grateful integration”.

“They aroused some hostility,” he says. “They were here and the war at that time was not going so well. But people did twig that they weren’t Nazi Germans and that the war wasn’t good for them either.”

But there was also some isolation for the children at the school, who were cut off from what they knew and from their families. There is a grave in Wem still for a young boy Martin Solmitz, who committed suicide at the school.

The school stayed in Trench Hall until 1946, when it returned to Kent, but only lasted two years more as Anna Essinger’s eyesight deteriorated and the cohort of staff were again free to move and teach elsewhere.

“It was an utterly unique situation in the country,” says Alastair. “The teaching staff were looking for a familiar sense of hope and surroundings, and that is what the school offered at that time.”

Now Trench Hall is used as part of The Woodlands Centre, a specialist school, but a blue plaque still points to the unique role this corner of Shropshire played in rescuing young Jewish people from the horrors of Nazi Germany.