Halloween: How stateside razzamataz began as a very British tradition

It's tempting to blame the Yanks. Trick or Treat, witch's outfits in every supermarket, kids in zombie make-up carrying pumpkin Jack O'lanterns.

We never had all this razzamataz 30 or 40 years ago, when Halloween was largely ignored.

But while the Americans have done what Americans do, and turned it into big business, Halloween is very much a British export, with its roots largely in Scotland and Ireland.

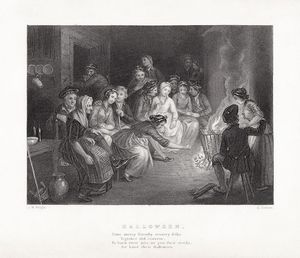

The term Halloween was first used about 1745, and a contraction of the Scottish All Hallows' Even, the night before All Saints' Day. In his poem of 1785 entitled Halloween, Robert Burns observed: "Some merry, friendly, countra-folks, Together did convene, To burn their nits, an' pou their stocks, An' haud their Halloween."

While the modern Halloween festival has its roots in Christianity, much of the imagery associated with it comes from the earlier Celtic pagan traditions, including the Gaelic harvest festival of Samhain which was observed on the same day.

Samhain was the night the Celts believed the veil separating the worlds of the spirits and the living was at its thinnest, allowing the supernatural forces to come cause mischief or harm. They believed people were transformed into cats as a punishment for their bad deeds, and that those unfortunate enough to be cursed by black magic were also turned into cats, particularly black cats.

The Celts also marked Samhain by holding large bonfires to ward off evil spirits, which attracted flying insects, which turn attracted the bats. The silhouette of the bats from the firelight soon became a feature of the Halloween tradition.

Following the Roman conquest, many Celts converted to Christianity, but there was some overlap between the two belief systems. Witches, who the ancient Celts believed were sources of wisdom and medicine, were portrayed as sinister devil-worshippers, who many believed could turn into black cats, as well as other animals such as bats and spiders.

When it comes to trick-or-treating, where children go from door to door asking for sweets, the United States actually arrived pretty late to the party. The custom has its origins in the tradition of 'souling', which began in Great Britain and Ireland around the 15th century, and spread across northern Europe, but did not reach the US until the early 20th century.

WATCH: Check out pumpkin carver Simon Patel's ghoulish design

In the early days, people would visit houses and ask for soul-cakes, either as symbols of the dead, or in return for praying for their souls. Later, people went from parish to parish at Halloween, begging soul-cakes by singing under the windows. It was mentioned by Shakespeare in 1593 when, in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Speed accuses his master of "puling like a beggar at Hallowmas".

By the 16th century, the practice of "guising", or wearing disguises while going door to door had also been recorded in Scotland, and quickly spread to other parts of Great Britain and Ireland. 'Mumming', where people would perform short plays in exchange for money or food, also became more common.

These traditions continued to grow during the 18th and 19th centuries, when they began to take on a more sinister dimension. In parts of southern Ireland, a man dressed as a white horse would lead youths house to house reciting verses – some with pagan overtones – in exchange for food. Householders were told that if they donated food, they could expect good fortune from the 'Muck Olla', but if they refused to do so, they would suffer misfortune.

In Scotland, youths knocked on doors dressed in white with masked or painted faces, reciting rhymes and often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed. In parts of Wales, peasant men went house to house dressed as fearsome beings called gwrachod, and it was also common in the counties of the West Midlands close to the Welsh border.

According to one 19th century English writer: "parties of children, dressed up in fantastic costume, went round to the farm houses and cottages, singing a song, and begging for cakes, apples, money, or anything that the goodwives would give them."

The earliest recording of the practice in North America did not come until 1911, where a newspaper in Kingston, Ontario, Canada reported children going 'guising' around the neighbourhood.

But while the Americans were late to adopt the traditional Halloween customs, they did leave their mark. While the custom of making Jack O'Lanterns from hollowed out turnips and mangel wurzels is thought to have originated in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands in the 19th century, the Americans instead used pumpkins, which were more traditionally associated with the Thanksgiving festival. The first recorded use of the term 'Trick or Treat' came in Canada in 1927, but it did not reach the US until 1932.

But while the early 20th century saw a rise in the popularity of Halloween in the US, it also coincided with a decline in interest in England and Wales. The traditions of 'guising' and 'mumming' had by this time largely been superseded by those associated with Guy Fawkes' Night. American historian Ruth Edna Kelley, from Massachusetts, in her 1919 publication The Book of Hallowe'en, observed that the Americans were seeking to restore the old traditions to their former glory.

She wrote: "Americans have fostered them, and are making this an occasion something like what it must have been in its best days overseas. All Halloween customs in the United States are borrowed directly or adapted from those of other countries."

How ironic, then, that over the past couple of decades that Halloween appears to be slowly usurping the tradition of Guy Fawkes' Night.