Flashback to 1994: Military takeover of Stokesay Court leads to treasure trove discovery

During the war many a grand country mansion was requisitioned by the military, leaving the displaced occupants with no choice but to grin and bear it.

But at Stokesay Court in south Shropshire it was to lead to an extraordinary sequel over 50 years later.

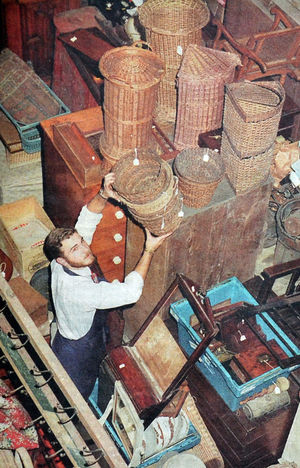

With the military having a reputation for not necessarily being the most careful custodians of precious contents, an operation was launched at Stokesay Court in 1941 to pack everything up and put it safely into storage.

So around 5,000 objects, including paintings, furniture, glass and ceramics, were moved into attics and cellars.

Carefully wrapped, and away from sunlight which could fade paintings and fabrics, they were in pristine condition when they were rediscovered by relatives over half a century later, their colours as bright as the day they had been hidden away.

Fine art dealer Robert Holden said at the time: “No-one had any inkling that there was an Aladdin’s cave untouched.’’

This really was a case of cash in the attic. A four-day auction of this treasure trove which began on September 28, 1994, created an international sensation and attracted buyers from around the world.

Dubbed "Shropshire's sale of the century" it was expected to raise £2.5 million, but that figure was comprehensively smashed and the total amount raised was £4,217,644 as the collection went under the hammer.

The sale was conducted by Sotheby’s at the late Victorian mansion near Onibury and was Britain's biggest country house sale for years.

A helicopter pad was set up in the grounds, along with a courtesy bus for VIPs. And as it opened it quickly became clear that bidding would be feverish, with early lots going under the hammer for twice their expected prices.

Over 1,000 people packed marquees and phone lines were red hot as bids came in thick and fast from across the world.

Up to 12 computers were linked to a mainframe in New York to deal with the huge amounts of money winging across the globe.

The range of items was extraordinary, including paintings bought direct from Royal Academy exhibitions, and souvenirs collected by Herbert Allcroft, the son of the man who had built the house, as he travelled widely in the 1890s.

It is said that on one trip to the Far East he and his wife bought the entire contents of Mr Beaton's Curio Store in Mandalay and several sets of Japanese armour.

The items stashed away in the attic and cellars also included a flag captured during the Indian Mutiny in 1857. Even a turtle's fin was to go under the hammer.

A set of 12 Victorian chairs, expected to fetch up to £6,000, sold for £28,000. A Victorian oak letter box, expected to make up to £2,500, actually made £6,000. A late George III mahogany clock went for almost twice the estimate of £2,500.

And so on.

The most valuable piece of furniture was an important French Louis XIV boulle commode dating from around 1710, which was expected to fetch up to £120,000. This however proved to be one of the disappointments, as bidding stopped at £80,000.

The operation to pack everything away during the war had been organised and supervised by Margaret Allcroft, known as Cissy, the chatelaine of Stokesay Court, which was being taken over to become a major training centre for the Home Guard.

The family retreated into one of the wings.

Cissy died in June 1946 and her daughter Jewell and her husband Philip Magnus, a famous biographer, went to live there.

They had no children, and they only furnished the hall and two of the public rooms, living fairly simply while the rest of the mansion slowly crumbled around them.

It meant that the stuff in the attic and cellars was never retrieved.

Jewell, Lady Magnus-Allcroft, became increasingly reclusive and refused to let anybody go into the cellars and attics.

Widowed in 1988, she died on June 18, 1992, at the age of 85, without telling anybody about her will, in which she left £4.8 million.

It was only after her death that the treasure trove was found, and was a complete surprise to the executors.

The house was left to a number of beneficiaries including her husband's niece, Caroline Magnus, and was completely empty when she moved in in 1995 after the sale.

She was to spend the next decade undertaking infrastructure repairs and refurnishing the interiors.