Leeches and goose fat – a delve into the weird and wonderful history of medicine

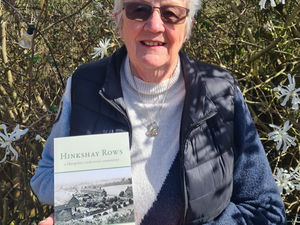

In the last months of my grandfather’s long life, the former miner implored us to put our faith in ancient, traditional therapies.

The octogenarian we unkindly dubbed Spider-Man – not because he possessed superhero powers, but because he struggled badly to get out of the bath – implored us to rub goose grease on his chest and back.

My, the old man went downhill fast after that.

An old chestnut, but one that illustrates the remedies, potions and bizarre panaceas ailing individuals in this region turned to before the National Health Service banished madness from medicine.

Many old fashioned cures are celebrated at the like of the Black Country Museum, where visitors can browse an array of baffling medicines and powders.

Sometimes old-fashioned quackery tripped on a legitimate cure: Leeches are used today in hospitals.

But often, the chemists’ “cure-alls” were deadlier than the disease.

And such a catalogue of now banned Class A narcotics were available over-the-counter in powders, lozenges and syrups that Victorian Britain had no need for backstreet drug dealers.

The prescriptions may not have cured hacking coughs, pounding headaches, throbbing toothaches or angry rashes, but those who took them were lost in such a poppy impregnated stupor they no longer cared.

Back then, the pharmaceutical industry was built on strange decisions, and, in 2024, I’m still baffled by the marketing strategies.

Take 'Nurofen Express', which pledges speedier relief than the brand previously provided. On the basis all customers want their pain to subside as quickly as possible, the product surely makes Nurofen original redundant. I do not believe individuals tell their chemist: “I’ve got this headache, but I’m fine with it at present.

“Got something that will remove it in a couple of days?”

Yet the two products sit shoulder-to-shoulder on shelves.

It is a weird science. At the turn of the 20th century, it was a downright wacky science that peddled cigarettes to ease bronchitis. In fairness to those who manufactured Dr Batty’s Asthma Cigarettes, sold under the slogan “for your health”, packaging carried the warning: “Not recommended for children under six.”

Before it became a highly addictive party drug for the champagne set, working class families ensured there was always cocaine in the medicine cabinet.

Admittedly an American product, Lloyd Manufacturing Company’s Cocaine Toothache Drops carried a picture of two children playing blissfully in the garden, a white picket-fence shielding their innocent antics.

After the drops, they were possibly a tad hyper-active.

Cocaine infused wine – a snarling Sanatogen tonic of its day – was, according to makers, guaranteed to “stimulate our lethargy and console our grief”.

One glass and sparks would fly from gran’s knitting needles.

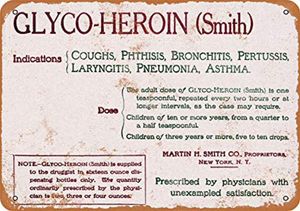

Smith’s 'Heroin Cough' may have been purchased to open blocked airwaves, but no doubt helped West Midlands men endure back-breaking factory graft and poverty with a vacant smile.

A mix of glycerine and heroin, makers boasted: “No other preparation has had its therapeutic value more highly defined or better established.”

Understandably, workers craved the opium-based substance. Children slept well – and deeply – after taking it.