From Soviet spy to the disappearing man: How ex-MP John Stonehouse still fascinates

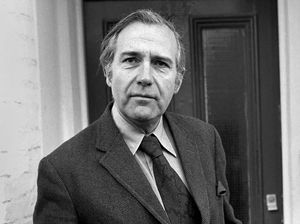

It is 62 years ago today that John Stonehouse, the most infamous Black Country politician to ever live, took his first steps into parliament as an MP.

A canny political operator with fierce ambition, Stonehouse seemed destined for the top. It was not a stretch for many to label him as a future Prime Minister.

But two decades later he was a national disgrace, had unsuccessfully faked his own death, and been jailed for fraud, all while spying for Britain’s Cold War nemesis.

So just where did it all go wrong for the real-life Reggie Perrin?

Political roots

Born into a political family – his mother a former mayor and councillor in Southampton and his father a trade unionist – Stonehouse moved into politics aged 16 when he joined the Labour party.

Educated at the London School of Economics, Stonehouse gained a particular interest in third-world countries, managing the African co-operative society in Uganda between 1952 and 1954.

The former RAF pilot, who served from 1944 until 1946, tried unsuccessfully to become an MP in 1950 in the seat of Twickenham and 1951 in Burton.

But he was elected to the now defunct ward of Wednesbury in 1957 as an MP for the Labour Co-operative party. He was 32.

Expelled

Within two years he was expelled from Rhodesia after criticising the white minority government of Southern Rhodesia and encouraging black residents to stand up for their rights.

But his knowledge of third-world countries would prove crucial when he wanted to expand his income.

His stance on ethnic minorities won him good support back home as his career began to take off. But before Stonehouse, who boasted an IQ of 140, got his first big break as a junior minister in 1964, his head had been turned.

Whether he was snared by a homosexual honeytrap or was simply a “chancer”, as Labour MP Dennis Skinner suggested, in 1962 Stonehouse began spying for Czechoslovakia.

Communist Czechoslovakia had been occupied throughout the Second World War by Nazi Germany and became part of the Soviet Union’s Eastern Bloc when Europe was divided up after 1945.

As America and the Soviets tussled for world dominance during the Cold War, Britain, an ally of the US through NATO, sided with the former.

Crucial information

The information he could pass on began to ramp up when he was made a Junior Minister for Aviation.

It is alleged he was paid £5,000, the equivalent of nearly £71,000 in today’s money, for crucial information on Britain’s planes and future aviation plans.

With the British government unaware of Stonehouse’s extra-curricular activity, the promotions continued.

He was made Minister of State for Technology in 1967. A year later he was made Postmaster General, which saw him looking after Britain’s postal system – he was the last man to ever hold the title, and during his tenure he introduced the first and second class mail system.

The same year he was appointed to the Privy Council – a body of advisers to the Queen.

In 1969 Josef Frolik, an ex-Czech spy who had defected to the US, outed Stonehouse to security services.

The MP was left fighting for his career but remained calm under questioning by MI5’s infamous Cold War officer Charles Elwell, in the presence of Prime Minister Harold Wilson.

He was questioned twice, and extensively so, but denied all the allegations. But his reprieve was short lived.

Fall out

When Labour lost the 1970 election to Edward Heath’s Conservatives, Stonehouse had an almighty falling out with Wilson.

He was booted out of the shadow cabinet and lost the extra money that came with a shadow ministerial position. He was also now no use to Czechoslovakia and the spy money dried up.

He decided to put his economics degree to good use and turn to the business world.

He set up several businesses across the globe, including an investment bank in Bangladesh, but these failed spectacularly.

He was left with debts rumoured to be about £800,000 – more than £10 million in modern money. With Wilson clinging to the Labour leadership, Stonehouse’s hopes of a glittering political future were blocked.

So Stonehouse got creative. He used the signature of his secretary-turned-lover Sheila Buckley to forge documents and listed her as a director on the majority of his companies.

But he knew this was a temporary fix, and began plotting his escape.

Death

The real-life Reggie Perrin planned to fake his own death, before assuming the identity of Joseph Markham, the dead husband of a constituent, and running off into the sunset.

He spent months planning it and on November 20, 1974, with a centre parting and thick spectacles, he left a pile of clothes on a Florida beach and vanished. He flew to Australia, assumed another new identity, that of another dead constituent called Clive Mildoon, and rendezvoused with Miss Buckley.

With no idea about his affair, Stonehouse’s wife presumed he had committed suicide. So did most others.

And with inflation heading towards 26 per cent and unemployment set for a 30-year high, Wilson, who was PM again, had no time to sweat over the missing Stonehouse.

A ceremonial service was held in the House of Commons and that was that. Stonehouse was gone. But another famous disappearance scuppered his plans.

Lord Lucan had gone missing two weeks before Stonehouse on November 7, the night the nanny of his children Sandra Rivett was bludgeoned to death at his former family home. Lady Lucan was also attacked.

Lucan, who was assumed to be the perpetrator, was an incredibly high-profile figure in the UK at the time, known for his lavish lifestyle and expensive taste. The interest in finding him was astronomical.

So when police in Melbourne were tipped off about a handsome, well-spoken Englishman shuttling large sums of money into a bank account from abroad, alarm bells rang.

Police raided the man’s address and forced him to pull his trousers down, as Lucan had a six-inch scar on his right inside thigh.

There was no scar and the well-spoken Englishman was not Lord Lucan. He was John Stonehouse.

Arrest

He was arrested and interviewed and his story quickly began to unravel as police discovered he’d entered the country on a false passport.

Soon he was up in court where his real identity was exposed.

But Stonehouse sought asylum in both Sweden and the Mauritius as Britain fought for six months to have him extradited.

Even when he was returned to the UK he had no intention of resigning as an MP and a Labour government that was clinging onto power faced the prospect of letting the Conservatives in if he was sacked.

Here was a man who had faked his own death and was in prison in Brixton, but remained MP for Walsall North, which had consumed his Wednesbury seat in 1974.

Released from prison on bail in August 1975, a brazen Stonehouse gave a speech in the House of Commons two months later.

He vehemently denied being a Czech spy, as he had six years previously, and blamed a mental breakdown for attempting to fake his own death.

He declared: “I assumed a new parallel personality that took over from me, which was foreign to me and which despised the humbug and sham of the past years of my public life.”

On April 7 1976, he finally resigned the Labour whip, around the same time his trial for charges of fraud, theft, forgery, conspiracy to defraud, causing a false police investigation and wasting police time got underway.

68-day trial

Refusing a lawyer and representing himself, Stonehouse’s trial lasted 68 days.

On August 6, 1976, he was found guilty of 18 counts of fraud, deception and theft and jailed for seven years. He was locked up in Wormwood Scrubs.

Eleven days after his conviction on August 17, Stonehouse resigned as a member of the Privy Council – becoming one of only three people in history to voluntarily give up his The Right Honourable title. Ten days later he finally resigned as an MP.

He tried to appeal five of his convictions in 1977 but the House of Lords refused.

On August 14 1979 Stonehouse was released early from prison for good behaviour.

While inside he had suffered three heart attacks, undergone open heart surgery and been divorced by Barbara.

But he was still alive, had Miss Buckley – soon to be Mrs Stonehouse – by his side and still no one knew of his Cold War treachery.

In September 1980, Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government learnt from a second Czech defector about Stonehouse’s spying. With insufficient evidence and the defector declining to appear in court, the government kept quiet.

So Stonehouse remained in the public eye and even returned to politics. He made several radio and TV appearances discussing his disappearance and joined the Social Democratic Party.

He also set up a small firm manufacturing electronic hotel safes.

Stonehouse collapsed in Birmingham while appearing on Central Live to talk about missing people on March 25, 1988. He survived, but on April 14 he was admitted to Southampton General hospital after suffering his fourth heart attack.

Aged 62, he was pronounced dead at 2.30am on April 14, 1988.

It was not until 22 years later when previously classified documents were released that the truth finally came out.

John Stonehouse was not just a failed politician, a bad businessman and the man who could not make it all go away – he was also a spy.