Could this 130,000-year-old mastodon skeleton really rewrite human history?

Paleontologists say they have found new evidence to support their claim but not everyone agrees…

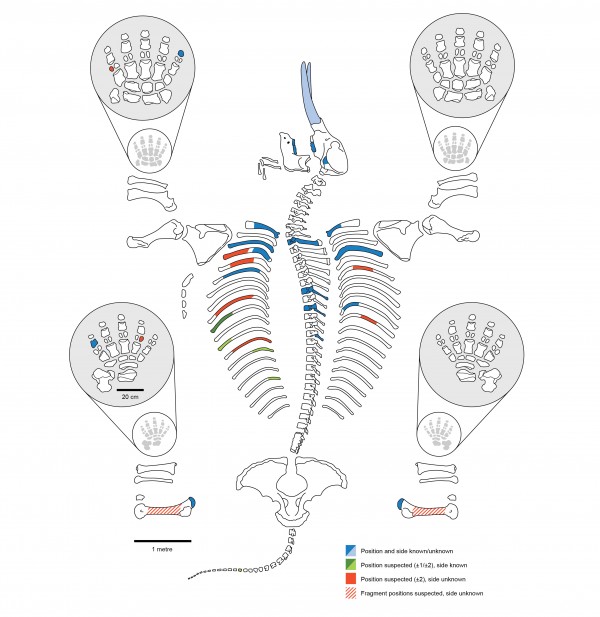

Paleontologists have pieced together a 130,000-year-old mastodon skeleton that they believe was bludgeoned by humans. If their theory proves correct, it could potentially turn our understanding of human migration upside down.

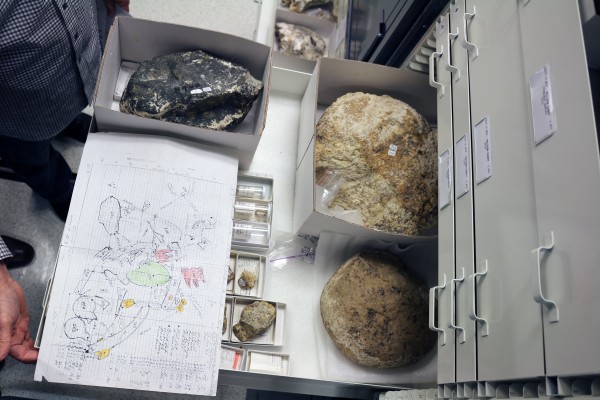

The fossil remains were found in San Diego, California, buried deep underground alongside large stones that researchers believe may have been used as tools.

However, according to today’s narrative of human migration, humans were not supposed to have arrived in America for another 100,000 years.

If their conclusions are proved correct, it could potentially rewrite human history.

Judy Gradwohl, CEO of the San Diego Natural History Museum, whose research team conducted the excavation, said: “This discovery is rewriting our understanding of when humans reached the New World.

“The evidence we found at this site indicates that some hominin species was living in North America 115,000 years earlier than previously thought.

“This raises intriguing questions about how these early humans arrived here and who they were.”

The site was first found in 1992. Paleontologists excavated the mastodon skeleton, along with oddly shaped rocks and the bones of other extinct animals.

It took the researchers a quarter of a century to piece the fossils together and use modern radiometric dating methods to determine the skeleton was around 130,000 years old.

Distantly related to elephants, mastodons inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene period.

Examining the marks and pattern of breakage on the on the skeleton and the tusks, the paleontologists say it is likely they were taken apart and broken with stone tools.

However, other researchers have challenged the findings.

“My first reaction on reading this paper was ‘No. This is wrong. Something’s wrong,’” stone tool expert John McNabb, of the University of Southampton, told NBC News.

“If it does turn out to be true, it changes absolutely everything.”

Archaeologist Donald Grayson, of the University of Washington, told the New York Times: “I was astonished, not because it is so good but because it is so bad.”

He said the study failed to rule out natural causes or other possible explanations for the markings on the bones.

The researchers involved in the excavation are inviting other scientists to review their findings.

The report is published in the journal Nature.