Physicists create the brightest light ever produced on Earth

It’s a billion times brighter than the sun.

A laser has produced the most dazzling light ever made on Earth – one billion times brighter than the surface of the sun.

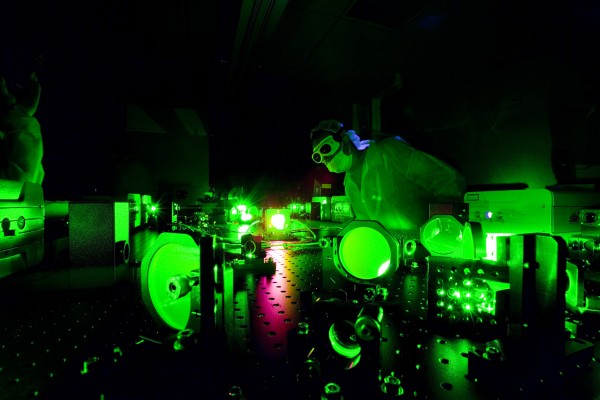

Scientists at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in the US fired an ultra high-intensity laser known as “Diocles” at electrons suspended in helium.

The aim was to study how photons from the laser scattered from single electrons.

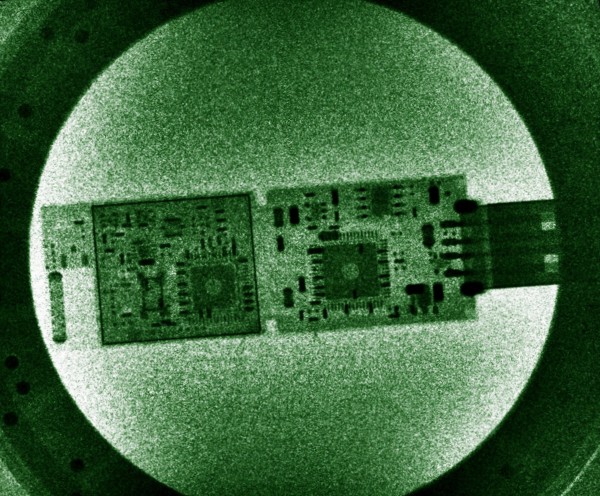

The extreme brightness sparked a phenomenon never seen before: unique X-rays that could be used for super-sensitive medical scans and security systems.

It is the scattering of light from a surface that makes vision possible, but in this case the high number of scattered photons, almost 1,000 at a time, produced results that turned nature on its head.

Professor Donald Umstadter, from the university’s Extreme Light Laboratory, said: “When we have this unimaginably bright light, it turns out that the scattering – this fundamental thing that makes everything visible – fundamentally changes in nature.”

Above a certain threshold, the laser’s brightness altered the angle, shape and wavelength of scattered light.

“It’s as if things appear differently as you turn up the brightness of light, which is not something you normally would experience,” said Prof Umstadter.

The effect of so many scattered photons was the creation of X-rays with unique properties.

The X-rays generated by the laser beam hitting the electrons were powerful but lasted an incredibly short length of time and were held within a narrow energy range.

The scientists believe they could form the basis of low-dose but highly sensitive 3D X-ray scans for tracking down elusive tumours or mapping the molecular landscape of nanoscale materials.

The research is published in the journal Nature Photonics.