Jellyfish robots could be ‘guardians of the oceans’

Soft ‘jellybots’ could be used to explore and study fragile environments without damaging them, say scientists.

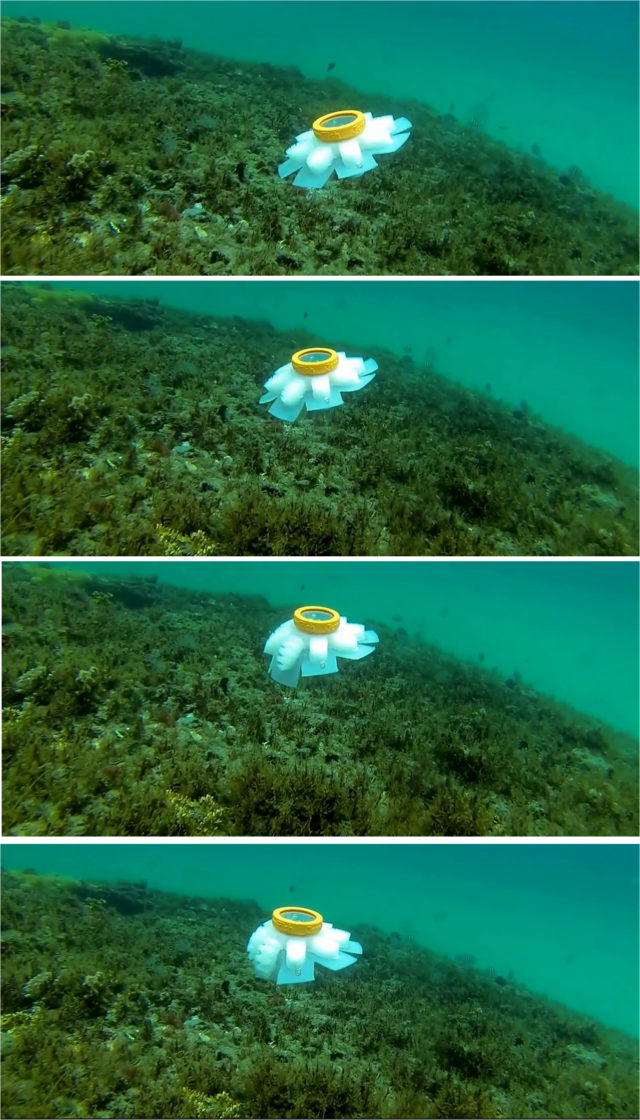

Soft robot jellyfish that can swim through openings narrower than their bodies could be used to monitor fragile coral reefs, say scientists.

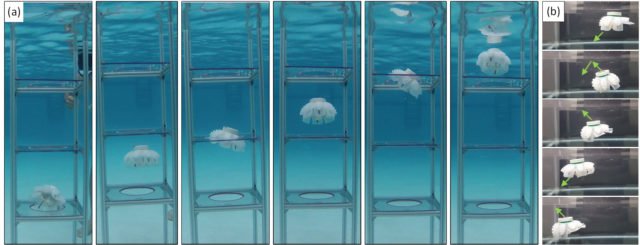

Several of the robots, propelled by hydraulic-powered tentacles, have been tested squeezing through holes cut in a plexiglass plate.

In future the “jellybots” could be sent into delicate environments, such as coral reefs, without risking collision and damage.

Their creators believe they could act as “guardians of the oceans”.

Dr Erik Engeberg, one of the robot’s inventors from Florida Atlantic University in the US, said: “Studying and monitoring fragile environments, such as coral reefs, has always been challenging for marine researchers. Soft robots have great potential to help with this.”

The design of the jellybot is based on the shape of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) during the larval stage of its lifecycle.

To allow the robot to swim and steer the team used a hydraulic system driven by two impeller pumps.

Pumped water from the surrounding environment is used to inflate the jellybot’s eight silicon rubber tentacles to produce a swimming stroke.

When the pumps are not powered, the tentacles’ natural elasticity pushes the water back out.

Dr Engeberg said: “Biomimetic soft robots based on fish and other marine animals have gained popularity in the research community in the last few years. Jellyfish are excellent candidates because they are very efficient swimmers.

“Their propulsive performance is due to the shape of their bodies, which can produce a combination of vortex, jet propulsion, rowing, and suction-based locomotion.”

He added: “A main application of the robot is exploring and monitoring delicate ecosystems, so we chose soft hydraulic network actuators to prevent inadvertent damage.

“Additionally, live jellyfish have neutral buoyancy. To mimic this, we used water to inflate the hydraulic network actuators while swimming.”

Five jellybots with varying levels of hardness were produced for the tests using 3D printing techniques.

“We found the robots were able to swim through openings narrower than the nominal diameter of the robot,” said Dr Engeberg.

Future robots will have environmental sensors and navigational programming to help them find gaps and decide if they can swim through them.

The research is published in the journal Biomimetics and Bioinspiration.