Regions see jump in top A-level grades but experts warn inequalities remain

A-level results show every region in England has seen a year-on-year increase in the proportion of A-level entries awarded an A* or A grade.

Every region in England saw an increase in top A-level grades this summer, but there are warnings that stark divides in achievement remain.

There is still a “two-tier” system in A-level results, with students in London and the South East more likely to pick up the highest grades than their peers in other parts of the country, according to one social mobility expert.

Lee Elliot Major, professor of social mobility at Exeter University, said more must be done to create a level playing field to allow all teenagers to reach their potential, regardless of where they live.

Exam figures for 2024 show every region of England has seen a year-on-year increase in the proportion of A-level entries awarded A and above.

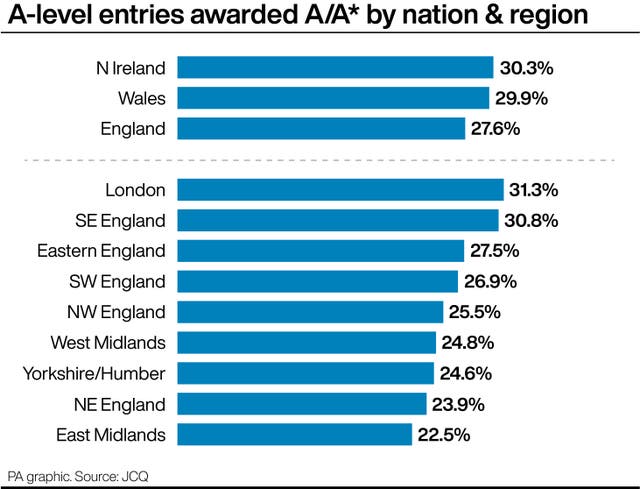

All regions also saw a higher proportion of entries awarded A* or A this year compared with the pre-pandemic year of 2019, but London and south-east England were the only areas to see figures above 30%, with the next highest region – eastern England – some way behind on 27.5%.

London saw the highest proportion of entries awarded A and above, at 31.3%, up 1.3 percentage points from 30.0% in 2023.

The East Midlands had the lowest, at 22.5%, up 0.2 points from 22.3% in 2023.

The gap between these two regions was 8.8 percentage points, up from 7.7 points last year.

Prof Elliot Major told the PA news agency: “These results highlight the stark regional divides that characterise our education system.

“When it comes to A-level results, we effectively have a two-tier system: London and the South East versus the rest of the country.”

He added: “Of course these patterns reflect the differing levels of child poverty across the country, but we need to do more to understand the specific obstacles to education in different parts of the country.

“Our South West social mobility commission for example found that coastal and rural inequalities and lack of connectivity are particular problems in this region of the country.

“We must do better in creating a level playing field in which all teenagers can flourish academically, wherever they happen to come from.”

Earlier this week, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson pledged to turn around “baked-in” educational inequalities, to ensure young people from all backgrounds have a chance to “get on in life” after leaving school.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of school leaders’ union the NAHT, said the Education Secretary is right to look at these disparities.

He said: “Although the percentage of top A-level grades (A/A*) increased in all regions of England this year, looking behind the headline figures, the gap between the highest achievers in different regions has continued to grow.

“School leaders have seen both the pernicious impact of the pandemic and poverty on children’s learning, mental and physical health, and wellbeing.

“When families are struggling with insecure housing, or to afford to heat their homes and feed their children, this inevitably affects pupils’ ability to attend school and concentrate when they are there.”

Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “These figures are a sign of the deep inequalities in our society, and we welcome the new Government’s focus on tackling child poverty and disadvantage.

“This work will need to produce tangible results sooner rather than later.”

In 2023, north-east England had the lowest proportion of entries awarded A or above, at 22.0%, while south-east England had the highest, at 30.3%: a gap of 8.3 points.

But this year the gap between these two regions narrowed to 6.9 points (north-east England 23.9%, south-east England 30.8%).

Meanwhile, the proportion of entries awarded A and above in Wales and Northern Ireland has fallen sharply year on year, as these nations complete the return to pre-pandemic levels of grading.

In Wales, the figure has dropped from 34.0% in 2023 to 29.9%, while in Northern Ireland it has decreased from 37.5% to 30.3%, though both of these are still above the 2019 pre-pandemic figures of 26.5% and 29.4% respectively.

Here are the percentages of A-level entries awarded the top grades (A*/A) by nation and region, with the equivalent figures for both 2023 and the pre-pandemic year of 2019:

– North-east England 23.9% (2023: 22.0%; 2019: 23.0%)

– North-west England 25.5% (2023: 24.1%; 2019: 23.5%)

– Yorkshire & the Humber 24.6% (2023: 23.0%; 2019: 23.2%)

– West Midlands 24.8% (2023: 22.9%; 2019: 22.0%)

– East Midlands 22.5% (2023: 22.3%; 2019: 21.0%)

– Eastern England 27.5% (2023: 26.6%; 2019: 25.6%)

– South-west England 26.9% (2023: 26.3%; 2019: 25.8%)

– South-east England 30.8% (2023: 30.3%; 2019: 28.3%)

– London 31.3% (2023: 30.0%; 2019: 26.9%)

– England 27.6% (2023: 26.5%; 2019: 25.2%)

– Wales 29.9% (2023: 34.0%; 2019: 26.5%)

– Northern Ireland 30.3% (2023: 37.5%; 2019: 29.4%)

– All 27.8% (2023: 27.2%; 2019: 25.4%)

Here is the A-level pass rate (entries awarded A*-E grades) by nation and region:

– North-east England 97.6% (2023: 97.6%; 2019: 98.3%)

– North-west England 97.6% (2023: 97.4%; 2019: 97.9%)

– Yorkshire & the Humber 97.3% (2023: 97.2%; 2019: 97.8%)

– West Midlands 96.8% (2023: 96.8%; 2019: 97.1%)

– East Midlands 96.6% (2023: 96.9%; 2019: 97.4%)

– Eastern England 97.1% (2023: 97.3%; 2019: 97.6%)

– South-west England 97.4% (2023: 97.4%; 2019: 97.7%)

– South-east England 97.3% (2023: 97.5%; 2019: 97.8%)

– London 96.9% (2023: 96.9%; 2019: 96.8%)

– England 97.1% (2023: 97.2%; 2019: 97.5%)

– Wales 97.4% (2023: 97.5%; 2019: 97.6%)

– Northern Ireland 98.5% (2023: 98.8%; 2019: 98.4%)

– All 97.2% (2023: 97.3%; 2019: 97.6%)