Hillsborough disaster still casts shadow over football

Tragedy’s 30th anniversary passes with families still seeking answers.

It was a bright spring afternoon in south Yorkshire, and spirits were high.

As fans arrived for a hotly anticipated cup tie between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest, there was a carnival atmosphere in the Victorian terraces of the Sheffield suburb of Owlerton.

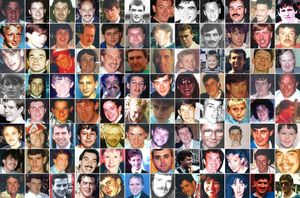

An hour later, the mood would change to one of heartache and chaos never seen before, as a devastating crush would leave 96 Liverpool fans dead and 766 injured.

It is 30 years today since the Hillsborough disaster, the worst disaster in British football history.

And three decades on the families of those killed are still seeking justice.

Questions still remain unanswered about the reasons for the tragedy, and in particular the police's handling of the crowds on the day.

It changed forever the way fans watch football, with the legendary huge standing areas such as the Kop, the South Bank and the Holte End consigned to history.

It wasn't the first crush at Hillsborough. Eight years earlier, there had been an incident at a cup semi-final between Wolves and Tottenham Hotspur, but although a number of supporters were injured, there were no fatalities. It led to the ground being removed from the FA's list of grounds suitable for semi-finals, but it was reinstated in 1987 following changes to the ground.

Liverpool and Forest had met at Hillsborough for the previous year's semi, and on that occasion British Rail had chartered three trains to bring fans to the ground. However, for the 1989 game, a single dedicated train was considered sufficient, resulting in 350 Liverpool fans arriving at the ground at 2.20pm. Roadworks on the M62 also delayed many fans, creating a bottleneck outside the stadium as kick-off approached.

The previous year, Liverpool fans had been located in the Spion Kop, the larger area at the eastern end of the stadium, as their team traditionally had the larger following. However, for this game they decided to allocate the Kop and the South Stand to Forest fans, who would be arriving at the game from the south, and allocated the smaller North Stand and Leppings Lane end to Liverpool supporters.

To keep the rival fans apart, a number of turnstiles were closed, meaning that all Liverpool fans were directed through the gates at the Leppings Lane stand.

This proved to be something of a bottleneck for fans entering the ground, and 20 to 30 minutes before kick-off crowds there was a build-up of thousands of fans outside Leppings Lane.

The previous year barriers had been installed outside the ground to slow down the crowds and allow tickets to be checked, but none had been erected this time. Concerned about the situation, a police constable radioed control asking for the game to be delayed by 20 minutes.

This had been done two years previously to give fans time to safely enter the ground, but this time the request was declined.

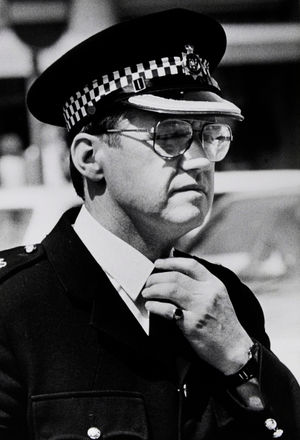

Instead, eight minutes before the game was due to start Supt David Duckenfield, the newly promoted and inexperienced match commander, made the fateful decision for the exit gates to be opened. This resulted in 2,000 fans surging into the ground.

One of the changes that had taken place at Hillsborough since the 1981 crush was that the Leppings Lane terrace had been divided into four separate enclosures, each separated by a fence.

A crush barrier in the tunnel leading to the pens was removed so fans could access the terraces more quickly. However poor signposting meant that most fans headed straight into the central pens behind the goal, through a tunnel directly ahead of them.

The inquests that followed would hear that signs for refreshments were more prominent than those showing fans how to get to pens one and two, at the sides of the stand.

The previous year, police dealt with that problem by posting officers inside the stand, to direct supporters away from the crowded central pens immediately behind the goal. However, this time there was no system to ensure an even distribution of fans, or even an attempt to count how many were in each pen. It was later revealed that 3,000 fans were in pens three and four on the day, almost double the number considered to be safe.

At 2.46pm – 14 minutes before kick-off – commentator John Motson observed the uneven distribution of supporters during a test broadcast, commenting on the large empty spaces at the side of the stadium.

Five minutes into the game, Liverpool forward Peter Beardsley hit the crossbar, leading to a surge forward in the central pen, causing a crush barrier to collapse.

Supporters shouted to the police for help, and some fans tried to climb over the fences designed to keep them off the pitch. But police initially thought it was a pitch invasion, and tried to push the supporters back into the crush.

At 3.06pm Supt Roger Greenwood, the man in charge inside the ground, realised what was happening and ran onto the pitch telling the referee to halt the match.

The situation descended into total chaos in the scenes that followed.

The police and ambulance services delayed declaring a major incident, while firefighters with cutting gear had difficulty getting into the ground. Dozens of ambulances were dispatched, but only two made it to the Leppings Lane end of the pitch because police had reported "crowd trouble".

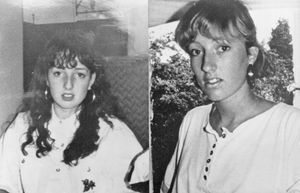

Among the 96 killed were Sarah and Victoria Hicks, the teenage daughters of Black Country businessman Trevor Hicks who battled in vain to give them mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

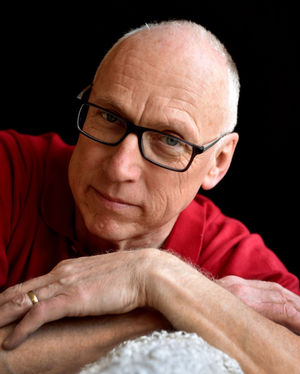

Mr Hicks, at the time managing director of Kingswinford-based Perma Systems, last month told a court how a police officer swore at him as he tried to raise the alarm.

He said he later spoke to a second police officer who did not respond. “We were helpless, we were just in the crowd and were in the hands of the organisers and the policemen,” he said.

The game had been a birthday treat after Sarah had turned 19 a few days before.

Mr Hicks thought he saw Victoria, 15, being carried out of the terrace so he left the pen and then found both girls on the pitch. He went in an ambulance to hospital with Victoria while Sarah was still being treated on the pitch.

“That was probably the worst moment of my life," he said.

“I had two daughters, only one with me. They both needed attention, we thought they were both alive. We put Victoria in. I turned to get Sarah. There was a few seconds, half a minute, where I was hesitating whether I should go or stay.

“The best thing to do was go with Victoria expecting that the other ambulance would follow and Sarah would be along very quickly.”

Walsall GP, Dr Colin Flenley, was in one the neighbouring pens at the side, and desperately tried to save Victoria and Sarah. He said he was ‘incensed’ when West Midlands Police, called in to investigate the Yorkshire force, seemed mainly concerned with asking him how much alcohol he had drunk.

“You could tell the central pens were absolutely packed," he said. "I have stood on the Kop for years and a big crowd sways and moves. This crowd was not moving at all."

Duckenfield later denied ordering the exit gate to be opened, claiming it had been forced by fans – a story he would maintain for 26 years, until finally admitting to a 'terrible lie'.

He was charged with manslaughter, but earlier this month a jury at Preston Crown Court failed to reach a verdict.

Today's multi-million pound all-seater s grounds are a world away from the grim squalor that was, until relatively recently, considered the norm.

But 30 years on, Hillsborough continues to cast a dark shadow over the beautiful game.