Visionary publisher Sonny Mehta dies at 77

The Cambridge graduate started his career in London before moving to New York, and was dubbed ‘the Fred Astaire of editing’.

Publishing giant Sonny Mehta, who guided one of the book world’s most esteemed imprints to new heights, has died at the age of 77.

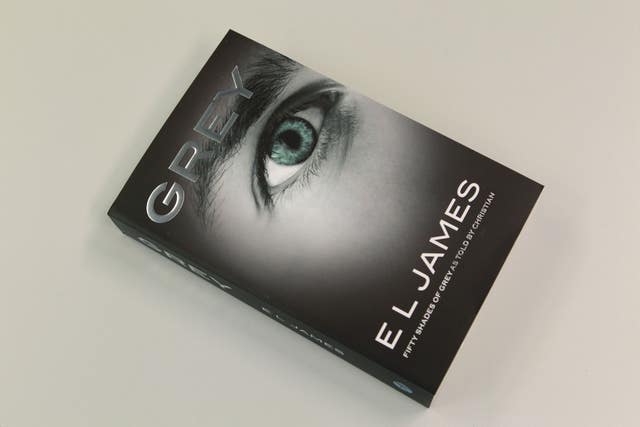

The urbane and astute head of Alfred A Knopf oversaw a blend of prize-winning literature by the likes of Toni Morrison and Cormac McCarthy and blockbusters such as Fifty Shades Of Grey and The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo.

Mehta, the husband of author Gita Mehta, died on Monday at his home in Manhattan. According to Knopf, the cause was complications from pneumonia.

The bearded, chain-smoking Mehta spoke carefully and chose wisely, helping Knopf thrive even as the industry faced the challenges of corporate consolidation, the demise of thousands of independent stores and the rise of e-books.

An accomplished publisher and editor since his mid-20s, he succeeded the revered Robert Gottlieb in 1987 as the third Knopf editor-in-chief in its 72-year history, and over the following decades fashioned his own record of critical and commercial success.

He continued to publish celebrated authors signed by Gottlieb, including Morrison and Robert Caro, while adding newer talent such as Tommy Orange, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Karen Russell.

Knopf also was home to some of the best-selling works in recent times. In 2008, Mehta acquired US rights to a trilogy of crime fiction by a dead Swedish journalist, Stieg Larsson’s Millennium series, which went on to sell tens of millions of copies.

In 2012, the paperback imprint Vintage won a bidding war for an explicit erotic trilogy that at the time could only be read digitally, EL James’s Fifty Shades novels.

Other top sellers released during Mehta’s reign included Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In, Bill Clinton’s My Life and Cheryl Strayed’s Wild.

When the Centre for Fiction honoured Mehta in 2018 with a lifetime achievement award, tributes were written by Joan Didion, Haruki Murakami and Anne Tyler, who praised “his precision” and “deft assurance” and called him the “Fred Astaire of editing”.

Knopf’s catalogue often reflected Mehta’s own broad curiosity. In a single season, the publisher might release new fiction by Morrison and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, crime novels by PD James and James Ellroy, poetry by Anne Carson and Philip Levine, history by John Keegan and Joseph Ellis, humour by Nora Ephron and memoirs by Clinton or Katharine Hepburn or Andre Agassi.

Knopf also appreciated the rewards of patience, allowing Caro to spend years between each instalment of his Lyndon Johnson biographies, a decades-long project that sold hundreds of thousands of copies and brought Caro numerous awards.

Mehta was born Ajai Singh Mehta, the bookish son of Indian diplomat Amrik Singh Mehta. He lived everywhere from Geneva to Nepal as a child and graduated from Cambridge University with degrees in history and English literature.

Choosing book publishing over his parents’ wishes he become a diplomat, Mehta needed little time to make an impact in London, helping to launch the literary career of his college friend Germaine Greer and introducing British readers to the profane Americana of Hunter S Thompson.

With Pan Books, he released works by rising authors such as Ian McEwan and Salman Rushdie, while signing up Jackie Collins, Douglas Adams and other best-sellers. He was Gottlieb’s personal choice to take over at Knopf, but still faced initial wariness from the staff.

“People … had the terrible fear that I was going to suddenly publish Jackie Collins over here and really sort of lower the tone of the place,” Mehta told Publishers Weekly in 2015.

“I think the difference was that I probably encouraged people to market a lot more than they were in the habit of doing. I encouraged them to look at a certain type of literary fiction and see it wasn’t necessarily intended for some kind of ghetto, that there was a bigger market for it.”